Questioning everything but me

Writing in the Niagara Anglican, Christopher M. Grabiec says that we know who won in the christological controversies of the 4th century leading to the creation of the Nicene Creed. But can we really know who was right? And does it really matter? Such questioning of core doctrinal formulations makes Grabiec sound supremely open-minded, but it does not prevent him expressing utter confidence in the truth of his own experience. If only the Nicene Fathers had had access to Grabiec's experience.

30 June 2008

26 June 2008

Authority and hierarchy

Anthony Esolen at Mere Comments speaks his mind in Between Obedience and Obedience. His remarks are relevant, of course, to my ongoing project on authority. I especially like his concluding paragraph:

That said, I myself would rephrase what comes before this, which is a defence of hierarchy against its detractors. Yes, hierarchical thinking, in the sense of making distinctions and ordering them mentally, is inevitable. So are hierarchies of authority, which no society can live without. History is littered with failed anarchist experiments in which a self-chosen few end up calling the shots at the expense of everyone else, despite the fact that mutuality was supposed to govern their relationships and activities. To deny hierarchies of authority is to open the door to would-be messiahs taking advantage of the lack of formal structures and procedures.

Nevertheless, Esolen's defence of hierarchy needs to be qualified in two ways.

In the first place, authority itself is something possessed by all human beings. This authority manifests itself most basically in the office of image-bearer of God, which entails a general call to exercise responsibility within and over his world (Genesis 1:28-30; Psalm 8). Beyond that, authority manifests itself in pluriform ways dispersed amongst persons in their multiple offices in the communities in which they are embedded.

Take the university community as an example. The professor obviously has magisterial authority over the class, setting its agenda, choosing the books to be read, scheduling the examinations and so forth. Yet even within the class students themselves possess the authority of students, which the professor is obliged to respect. Professors and students do not possess the same authority, but it is authority all the same. These two types of authority relate asymmetrically to each other, but they do not set up a permanent relationship of authority and subordination between the professor and students, either as persons or in their respective offices. To emphasize this, I insist that my own students, upon graduation, call me by my first name. We remain the same persons, but our professional relationship has changed for good: in their case the office of student has come to an end. My office of professor continues, but not with respect to the graduated alumni.

Furthermore, if one of my current students is a part-time traffic cop, then I am subject to her authority when I enter her intersection. She and I simultaneously bear several offices that relate to each other in different ways depending on context.

In the second place, a defence of hierarchy should not be taken to include ontological hierarchy, or the so-called Great Chain of Being of Plato, Aristotle and the neoplatonists. This conception is in stark contrast to the biblical worldview in two ways.

First and most fundamentally, it effaces the distinction between Creator and creation. If God is simply the ens perfectissimum, he is less than fully God. He may be seen to partake of something larger than himself, or the whole itself might be identified with God and its other components simply emanations from his own divinity. The resemblance to pantheism is obvious.

Second, the ontological hierarchy assumes that the lower levels of the chain differ from the higher levels in so far as the former partake more than the latter of evil, or nonbeing. As the Encyclopædia Britannica concisely puts it,

Here the legitimate diversity of God's creation is identified with the proliferation of multiple evils, even if they are ordered to a higher good. The beasts of the field are less perfect versions of us. We ourselves are imperfect versions of God himself.

This simply will not do. Scripture affirms that God created the diversity of the cosmos and pronounced it good. There is no hint that creation is an emanation from God himself or partakes of his essence. Moreover, sin is not nonbeing; it is living outside of communion with God and in defiance of his word. Sin has marred this communion. Salvation consists, not in our becoming God, but in receiving from him the restored wholeness proper to his image-bearing creatures.

Therefore we need not fear hierarchies of thought or hierarchies of authority, which are inevitable in any and every social context. These are best formalized and regularized than denied or dismissed. But we should certainly repudiate any hint of ontological hierarchy, which is a distortion of our relationship with God, each other and the rest of his creation.

Anthony Esolen at Mere Comments speaks his mind in Between Obedience and Obedience. His remarks are relevant, of course, to my ongoing project on authority. I especially like his concluding paragraph:

You obey, or you obey. On earth there is no third choice. The only question, ultimately, is whom. Christians are called to obey the God whose very commands set us free. The alternative is to heed somebody else, enjoy a petty and temporary license, and clap yourself in irons.

That said, I myself would rephrase what comes before this, which is a defence of hierarchy against its detractors. Yes, hierarchical thinking, in the sense of making distinctions and ordering them mentally, is inevitable. So are hierarchies of authority, which no society can live without. History is littered with failed anarchist experiments in which a self-chosen few end up calling the shots at the expense of everyone else, despite the fact that mutuality was supposed to govern their relationships and activities. To deny hierarchies of authority is to open the door to would-be messiahs taking advantage of the lack of formal structures and procedures.

Nevertheless, Esolen's defence of hierarchy needs to be qualified in two ways.

In the first place, authority itself is something possessed by all human beings. This authority manifests itself most basically in the office of image-bearer of God, which entails a general call to exercise responsibility within and over his world (Genesis 1:28-30; Psalm 8). Beyond that, authority manifests itself in pluriform ways dispersed amongst persons in their multiple offices in the communities in which they are embedded.

Take the university community as an example. The professor obviously has magisterial authority over the class, setting its agenda, choosing the books to be read, scheduling the examinations and so forth. Yet even within the class students themselves possess the authority of students, which the professor is obliged to respect. Professors and students do not possess the same authority, but it is authority all the same. These two types of authority relate asymmetrically to each other, but they do not set up a permanent relationship of authority and subordination between the professor and students, either as persons or in their respective offices. To emphasize this, I insist that my own students, upon graduation, call me by my first name. We remain the same persons, but our professional relationship has changed for good: in their case the office of student has come to an end. My office of professor continues, but not with respect to the graduated alumni.

Furthermore, if one of my current students is a part-time traffic cop, then I am subject to her authority when I enter her intersection. She and I simultaneously bear several offices that relate to each other in different ways depending on context.

In the second place, a defence of hierarchy should not be taken to include ontological hierarchy, or the so-called Great Chain of Being of Plato, Aristotle and the neoplatonists. This conception is in stark contrast to the biblical worldview in two ways.

First and most fundamentally, it effaces the distinction between Creator and creation. If God is simply the ens perfectissimum, he is less than fully God. He may be seen to partake of something larger than himself, or the whole itself might be identified with God and its other components simply emanations from his own divinity. The resemblance to pantheism is obvious.

Second, the ontological hierarchy assumes that the lower levels of the chain differ from the higher levels in so far as the former partake more than the latter of evil, or nonbeing. As the Encyclopædia Britannica concisely puts it,

The scale of being served Plotinus and many later writers as an explanation of the existence of evil in the sense of lack of some good. It also offered an argument for optimism; since all beings other than the ens perfectissimum are to some degree imperfect or evil, and since the goodness of the universe as a whole consists in its fullness, the best possible world will be one that contains the greatest possible variety of beings and so all possible evils.

Here the legitimate diversity of God's creation is identified with the proliferation of multiple evils, even if they are ordered to a higher good. The beasts of the field are less perfect versions of us. We ourselves are imperfect versions of God himself.

This simply will not do. Scripture affirms that God created the diversity of the cosmos and pronounced it good. There is no hint that creation is an emanation from God himself or partakes of his essence. Moreover, sin is not nonbeing; it is living outside of communion with God and in defiance of his word. Sin has marred this communion. Salvation consists, not in our becoming God, but in receiving from him the restored wholeness proper to his image-bearing creatures.

Therefore we need not fear hierarchies of thought or hierarchies of authority, which are inevitable in any and every social context. These are best formalized and regularized than denied or dismissed. But we should certainly repudiate any hint of ontological hierarchy, which is a distortion of our relationship with God, each other and the rest of his creation.

25 June 2008

Minor league baseball

As a nonbaseball fan, I have nevertheless attended more games than most people, and these have usually involved the Chicago Cubs or White Sox. Having personally known one player and hosted another at our family home in my youth, I had major league baseball as a part of my life for some years.

I do not recall ever attending a minor league game. Back in 1991 I did attend an exhibition game between a visiting Soviet (yes, Soviet, for a few more months!) team from Tiraspol and a local team from Geneva, Illinois. Around that time I learned that the ball park we were visiting would soon host a minor league team moving from Wisconsin. This became the Kane County Cougars, now a class A affiliate of the Oakland Athletics. At the time I thought the team should be called the Geneva Psalms, but obviously nothing came of that.

As far as I know, there is but one minor league team in Canada, the Vancouver Canadians. Even our own Toronto Blue Jays has farm teams only in the US and the Dominican Republic. The closest such team to us is the Buffalo Bisons, an affiliate of the Cleveland Indians, whose name and mascot have been a source of controversy in recent years.

There. Got that out of my system. This is probably my last post on baseball for another few years. Baseball fans should check back here in, say, 2013.

As a nonbaseball fan, I have nevertheless attended more games than most people, and these have usually involved the Chicago Cubs or White Sox. Having personally known one player and hosted another at our family home in my youth, I had major league baseball as a part of my life for some years.

I do not recall ever attending a minor league game. Back in 1991 I did attend an exhibition game between a visiting Soviet (yes, Soviet, for a few more months!) team from Tiraspol and a local team from Geneva, Illinois. Around that time I learned that the ball park we were visiting would soon host a minor league team moving from Wisconsin. This became the Kane County Cougars, now a class A affiliate of the Oakland Athletics. At the time I thought the team should be called the Geneva Psalms, but obviously nothing came of that.

As far as I know, there is but one minor league team in Canada, the Vancouver Canadians. Even our own Toronto Blue Jays has farm teams only in the US and the Dominican Republic. The closest such team to us is the Buffalo Bisons, an affiliate of the Cleveland Indians, whose name and mascot have been a source of controversy in recent years.

There. Got that out of my system. This is probably my last post on baseball for another few years. Baseball fans should check back here in, say, 2013.

22 June 2008

It's worth the drive to Hamilton

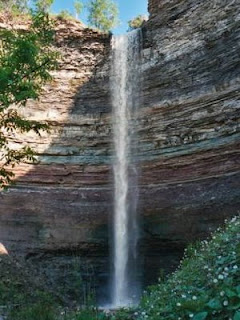

If you're looking for a place to spend your holiday, try the waterfall capital of the world.

Sherman Falls

Webster's Falls

Devil's Punchbowl

If you're looking for a place to spend your holiday, try the waterfall capital of the world.

21 June 2008

Ravel's hellenic foray

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) is one of my favourite composers. Thus when I came into contact with his Cinq mélodies populaires grecques more than two decades ago, I was intrigued.

The texts are apparently authentic Greek folk songs, though I am not persuaded, contrary to the person who posted this clip on Youtube, that this is true of the melodies as well. I have the sheet music somewhere, and I do recall seeing Greek and French texts between the staves. The tunes, however, were almost certainly composed by Ravel himself in what he believed to be the style of δημοτικά τραγούδια (folk songs). To my ears, however, they sound much more typically Ravel than Greek. Contrary to the writer of this review, the first song is not in G minor; this is modal music and it's in the G phrygian scale.

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) is one of my favourite composers. Thus when I came into contact with his Cinq mélodies populaires grecques more than two decades ago, I was intrigued.

The texts are apparently authentic Greek folk songs, though I am not persuaded, contrary to the person who posted this clip on Youtube, that this is true of the melodies as well. I have the sheet music somewhere, and I do recall seeing Greek and French texts between the staves. The tunes, however, were almost certainly composed by Ravel himself in what he believed to be the style of δημοτικά τραγούδια (folk songs). To my ears, however, they sound much more typically Ravel than Greek. Contrary to the writer of this review, the first song is not in G minor; this is modal music and it's in the G phrygian scale.

18 June 2008

Summer solstice snippets

There can be little doubt that the Bush administration has needlessly squandered the considerable international good will extended to the United States in the wake of 9/11. This study will only further harm America's already tattered reputation: Guantanamo detainees were tortured, medical exams show. Jim Skillen weighs in with his own response to this situation: Rule of Law Succumbs to Torture for Safety. Of course, this is not merely a matter of image, but of justice itself. Let us hope and pray that either McCain or Obama can see this more clearly than his predecessor.

Speaking of whom, if Rod Dreher is right about the lack of enthusiasm of Republicans for their own candidate, there could be a low voter turnout in November — low by even American standards. On the other hand, if Republicans dislike Obama more than they like McCain, we could see at least a small spike in the numbers of those flocking to the polls to vote against Obama. Perhaps I need a degree in psychology to figure this one out.

The Irish 'No' Leaves the European Union in a Fix. Um, haven't we seen this story before? Ask the French and the Dutch.

In the meantime Europeans and Canadians alike seem to be much more interested in this: Euro 2008. Though I've seen lots of cars with national flags flying from their antennae, I imagine their drivers are blithely unconcerned with the fate of the Lisbon Treaty.

I read this article shortly after it was published nearly a decade ago, but it is worth a second look: Why There is a Culture War: Gramsci and Tocqueville in America, by John Fonte. Despite his trenchant critique of the quasi-marxist influence of today's "Gramscians" in the US, it is not immediately evident that an affirmation of American exceptionalism, of which traditional religion is but one element, offers a sounder alternative.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper has offered a long overdue apology for Canada's unjust treatment of its aboriginal peoples. The political implications of this remain to be seen. It is no easy matter to come up with a resolution that will do justice to both our First Nations and our nonaboriginal citizens. Something like the wisdom of Solomon may be needed here.

A friend alerted me to this a while back: Taxes are a common good, by Chandra Pasma, on the website of Citizens for Public Justice. According to the author,

I recognize, of course, the problematic character of the word timeless, with its static connotations. Yet if political debate is simply a matter of citizens deciding collectively what they want government to do, that would seem to preclude a principled debate on what government ought to do.

Finally, it seems literary aspirations run in the family: The devil, God and Ronald Reagan. Could my young cousin be the next Stephen King?

Now I know there are disagreements about what the role of government should be in providing these goods and services. Certainly, the private sector and the voluntary sector have a role in many of these areas. But we should be able to have a public debate about what government’s role should be. After all, there are no timeless principles determining the role of government. Government is us, citizens, acting collectively. We have a right to decide what we do and do not want to do collectively.

I recognize, of course, the problematic character of the word timeless, with its static connotations. Yet if political debate is simply a matter of citizens deciding collectively what they want government to do, that would seem to preclude a principled debate on what government ought to do.

12 June 2008

What God has joined together . . .

Congratulations are due to my friends Stephen Lazarus and Judith Cooke on their wedding last saturday at Little Trinity Church in Toronto. Judith is a protégée of mine, having graduated from Redeemer in 2000 with a degree in political science. Up until now Stephen has worked for the Center for Public Justice in Annapolis, Maryland. I count it a privilege to have known both long before God brought them together.

And, yes, our family did ride the King Street car to the church, which I myself once regularly attended nearly three decades ago.

Congratulations are due to my friends Stephen Lazarus and Judith Cooke on their wedding last saturday at Little Trinity Church in Toronto. Judith is a protégée of mine, having graduated from Redeemer in 2000 with a degree in political science. Up until now Stephen has worked for the Center for Public Justice in Annapolis, Maryland. I count it a privilege to have known both long before God brought them together.

And, yes, our family did ride the King Street car to the church, which I myself once regularly attended nearly three decades ago.

Tram travel back on track?

If conservative political activist Paul Weyrich had his way, we'd all be riding the streetcars again. As a former resident of Toronto, where I happily rode the subways and streetcars for two years without the burden of an automobile, I heartily agree. Of course, not all of his fellow conservatives, especially those of a libertarian bent, will approve, but many will. Here in Hamilton we can only hope that our own Hamilton Street Railway will once again live up to its name.

If conservative political activist Paul Weyrich had his way, we'd all be riding the streetcars again. As a former resident of Toronto, where I happily rode the subways and streetcars for two years without the burden of an automobile, I heartily agree. Of course, not all of his fellow conservatives, especially those of a libertarian bent, will approve, but many will. Here in Hamilton we can only hope that our own Hamilton Street Railway will once again live up to its name.

America's future

Fareed Zakaria writes for Foreign Affairs: The Future of American Power: How America Can Survive the Rise of the Rest. One paragraph stands out for me:

Fareed Zakaria writes for Foreign Affairs: The Future of American Power: How America Can Survive the Rise of the Rest. One paragraph stands out for me:

Learning from the rest is no longer a matter of morality or politics. Increasingly, it is about competitiveness. Consider the automobile industry. For more than a century after 1894, most of the cars manufactured in North America were made in Michigan. Since 2004, Michigan has been replaced by Ontario, Canada. The reason is simple: health care. In the United States, car manufacturers have to pay $6,500 in medical and insurance costs for every worker. If they move a plant to Canada, which has a government-run health-care system, the cost to them is around $800 per worker. This is not necessarily an advertisement for the Canadian health-care system, but it does make clear that the costs of the U.S. health-care system have risen to a point where there is a significant competitive disadvantage to hiring American workers. Jobs are going not to low-wage countries but to places where well-trained and educated workers can be found: it is smart benefits, not low wages, that employers are looking for.

It can't happen here

Could this be true: Fascism has come to Canada? And this, not from an overtly nationalist or racist political party, but from a series of tribunals charged with protecting our human rights! David Warren summarizes the situation:

One hopes and prays that Catholic Insight and Warren are overstating their case. Nevertheless, it is clear that our historic right to freedom of speech, ostensibly protected by the Charter, is being eroded. If that ends up curtailing debate over important political issues, Canada's democracy will go with it.

Could this be true: Fascism has come to Canada? And this, not from an overtly nationalist or racist political party, but from a series of tribunals charged with protecting our human rights! David Warren summarizes the situation:

Among the spookiest aspects of these cases is the silence over, and indifference to them, on the part of journalists whose predecessors imagined themselves vigilant in the cause of freedom. As I’ve learned first-hand through email, many Canadian journalists today take the view that, 'I don’t like these people, therefore I don’t care what happens to them.' It is a view that, at best, is extremely short-sighted.

One hopes and prays that Catholic Insight and Warren are overstating their case. Nevertheless, it is clear that our historic right to freedom of speech, ostensibly protected by the Charter, is being eroded. If that ends up curtailing debate over important political issues, Canada's democracy will go with it.

05 June 2008

03 June 2008

Second-guessing America's founders

This is not officially part of my series on authority, but I thought I should take this opportunity to mention a book I've been reading, titled Civilizing Authority: Society, State, and Church, edited by Patrick McKinley Brennan. It contains a number of essays worth noting, especially "Society, Subsidiarity, and Authority in Catholic Social Thought," by Russell Hittinger, who defines subsidiarity in a remarkably (but, one assumes, inadvertently) Kuyperian direction; and "A Rock on Which One Can Build: Friendship, Solidarity, and the Notion of Authority," by Thomas Kohler, who comes strikingly close to Dooyeweerd's modal analysis. But the most intriguing essay comes from J. Budziszewski, who writes on "How a Constitution May Undermine Constitutionalism."

Two years ago in Ottawa I met a scholar who has spent much of his career analyzing the growing power of Canada's courts since patriation and its impact on our political system as a whole. Having recently visited Australia, I had noticed that something similar has occurred in that country, despite the absence of a justiciable bill or charter of rights. I asked this scholar why the expansion of judicial power appears to be so universal in western, and particularly English-speaking, democracies. His answer didn't stick with me, but I seem to recall that he was as puzzled as I at the underlying reasons for this phenomenon.

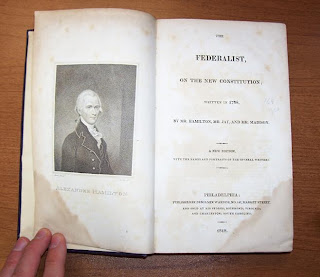

Budziszewski has now offered a compelling response, with a focus, to be sure, on the American context, but with implications for other federal systems as well, including those of Australia and Canada. Students of American government are generally familiar with the Federalist Papers, or The Federalist, a series of essays written, under the pseudonym Publius, in defence of the new federal constitution by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton and John Jay. The best known of these are numbers 10 and 51, the latter of which defends the internal checks and balances within the federal government itself.

By contrast, few Americans are aware of the Anti-Federalist Papers, written pseudonymously by opponents of the new constitution, one of whom took the name Brutus. Budziszewski focusses on numbers 11 and 12, where the author sets forth his reservations over the expansion of judicial power and its concomitant tendency to expand the legislative power as well. In particular, Brutus

It is a truism that the American founders fragmented government and distributed sovereignty among the three branches to prevent any one of them becoming tyrannical. This is what Americans have been taught for generations, the assumption being that the founders had a solid grasp of human nature and the tendency of people to compete with each other for various social and political goods. From my own American upbringing, I recall that Christians in particular viewed the founders as fellow believers who understood the sinfulness of man and thus placed checks in their proposed constitution to counteract its effects. This sounded good in theory. The founders were apparent realists in their estimation of human nature, while liberals and socialists of various stripes had an overly rosy view of man's potential.

Yet what if the founders too were working with a defective anthropology? Could they have imbibed a modified Hobbesian anthropology, perhaps by way of John Locke? Hobbes holds that human beings are creatures of restless desires and, left to their own devices, ruthless competitors for the means of survival. Hobbes famously argued that the prepolitical state of nature is characterized by a war of all against all. Locke, of course, could not bring himself to follow Hobbes' logic in its entirety, admitting only that the state of nature could degenerate into warfare if conditions were favourable. Hence the need for civil government to preside over this competition and to make it more manageable and less potentially deadly. As for government itself, its members are as prone as everyone else to compete for valued goods. Hence, following Montesquieu, the founders adopted a constitutional framework that would divide sovereignty amongst the three branches and between federal and state governments.

So many Americans have accepted this reasoning that they have difficulty imagining an alternative. Here is where, taking Brutus and Budziszewski as a springboard, I would make the following argument, which I believe is more congruent with a biblical worldview: the line between good and evil does not run between co-operation and competition, as so many have believed, but through each. Our own socialist New Democratic Party began life as the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, on the assumption that economic co-operation is better than the competition characteristic of capitalism. Yet those exalting solidarity over individuality ignore the fact that even organized crime is characterized by a certain solidarity amongst its perpetrators.

I would argue instead that both competition and co-operation have their legitimate places in human life. Competition can aim at narrow self-interest, but it can also be an incentive to service to others, as, e.g., in a charitable fund-raising marathon or even a large manufacturing enterprise supplying a needed good to the public. Similarly co-operation may be for the good of all, as socialists assume. But it can also be a means of collusion for purposes of price-fixing and other forms of corruption. Might the American founders have missed this element of human nature in their ostensibly "realistic" view?

Thus it may be that the expanding power of the courts has come with the blessing of the legislative branch. Here's Budziszewski again:

This is a conclusion I came to some time ago with respect to Canada. Since 1982 our courts have been making decisions that are increasingly imaginative and even in open conflict with the intentions of the drafters of the Constitution Act, 1982. We know this because, unlike the American founders, most of the players in the patriation drama are still very much alive! Given our convention of responsible government, a sitting government is reluctant to make decisions of a controversial nature. It is easier to leave such decisions up to the courts, who do not have to face the people. The Supreme Court's Reference re Québec secession is in many respects an ingenious decision that gave something to both sides and helped to prop up the federalist cause in Québec. Nevertheless, one would be hard put to demonstrate that the ruling was based on a close reading of our Constitution Acts, which nowhere mention secession.

Here in Canada we have Section 33, the Notwithstanding Clause, that legislators can invoke to override judicial decisions based on Sections 2 and 7-15 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Yet over the past quarter century few legislatures, with the exception of Québec's National Assembly, have been willing to invoke it. I believe Budziszewski, drawing on Brutus, has now given us a credible explanation for this reluctance.

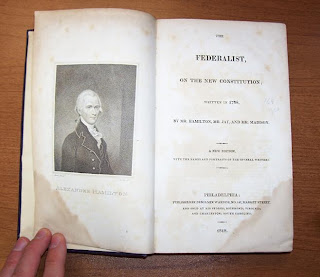

Incidentally, the copy of The Federalist shown above is from my personal library. It is a rebound edition dating from 1818, when two of the authors, James Madison and John Jay, were still alive.

This is not officially part of my series on authority, but I thought I should take this opportunity to mention a book I've been reading, titled Civilizing Authority: Society, State, and Church, edited by Patrick McKinley Brennan. It contains a number of essays worth noting, especially "Society, Subsidiarity, and Authority in Catholic Social Thought," by Russell Hittinger, who defines subsidiarity in a remarkably (but, one assumes, inadvertently) Kuyperian direction; and "A Rock on Which One Can Build: Friendship, Solidarity, and the Notion of Authority," by Thomas Kohler, who comes strikingly close to Dooyeweerd's modal analysis. But the most intriguing essay comes from J. Budziszewski, who writes on "How a Constitution May Undermine Constitutionalism."

Two years ago in Ottawa I met a scholar who has spent much of his career analyzing the growing power of Canada's courts since patriation and its impact on our political system as a whole. Having recently visited Australia, I had noticed that something similar has occurred in that country, despite the absence of a justiciable bill or charter of rights. I asked this scholar why the expansion of judicial power appears to be so universal in western, and particularly English-speaking, democracies. His answer didn't stick with me, but I seem to recall that he was as puzzled as I at the underlying reasons for this phenomenon.

Budziszewski has now offered a compelling response, with a focus, to be sure, on the American context, but with implications for other federal systems as well, including those of Australia and Canada. Students of American government are generally familiar with the Federalist Papers, or The Federalist, a series of essays written, under the pseudonym Publius, in defence of the new federal constitution by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton and John Jay. The best known of these are numbers 10 and 51, the latter of which defends the internal checks and balances within the federal government itself.

By contrast, few Americans are aware of the Anti-Federalist Papers, written pseudonymously by opponents of the new constitution, one of whom took the name Brutus. Budziszewski focusses on numbers 11 and 12, where the author sets forth his reservations over the expansion of judicial power and its concomitant tendency to expand the legislative power as well. In particular, Brutus

recognizes that a written constitution is not merely a statement of political ideals, but a legal instrument. It is all well and good to say that the three branches [legislative, executive and judicial] shall be coequal, but the courts normally interpret legal instruments. A differently drafted legal instrument might have distributed the power of interpretation among all three branches. It might have identified particular respects in which the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary are each interpreters of the constitution. What the Constitution actually does, argues Brutus, is just the opposite. Rather than distributing the power of interpretation, it concentrates it in the courts. To make matters worse, he holds, the language by which this is done encourages judges to exercise this concentrated power of interpretation in extravagant ways that bear but a distant relation to what the Constitution actually says (p. 148).

It is a truism that the American founders fragmented government and distributed sovereignty among the three branches to prevent any one of them becoming tyrannical. This is what Americans have been taught for generations, the assumption being that the founders had a solid grasp of human nature and the tendency of people to compete with each other for various social and political goods. From my own American upbringing, I recall that Christians in particular viewed the founders as fellow believers who understood the sinfulness of man and thus placed checks in their proposed constitution to counteract its effects. This sounded good in theory. The founders were apparent realists in their estimation of human nature, while liberals and socialists of various stripes had an overly rosy view of man's potential.

Yet what if the founders too were working with a defective anthropology? Could they have imbibed a modified Hobbesian anthropology, perhaps by way of John Locke? Hobbes holds that human beings are creatures of restless desires and, left to their own devices, ruthless competitors for the means of survival. Hobbes famously argued that the prepolitical state of nature is characterized by a war of all against all. Locke, of course, could not bring himself to follow Hobbes' logic in its entirety, admitting only that the state of nature could degenerate into warfare if conditions were favourable. Hence the need for civil government to preside over this competition and to make it more manageable and less potentially deadly. As for government itself, its members are as prone as everyone else to compete for valued goods. Hence, following Montesquieu, the founders adopted a constitutional framework that would divide sovereignty amongst the three branches and between federal and state governments.

So many Americans have accepted this reasoning that they have difficulty imagining an alternative. Here is where, taking Brutus and Budziszewski as a springboard, I would make the following argument, which I believe is more congruent with a biblical worldview: the line between good and evil does not run between co-operation and competition, as so many have believed, but through each. Our own socialist New Democratic Party began life as the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, on the assumption that economic co-operation is better than the competition characteristic of capitalism. Yet those exalting solidarity over individuality ignore the fact that even organized crime is characterized by a certain solidarity amongst its perpetrators.

I would argue instead that both competition and co-operation have their legitimate places in human life. Competition can aim at narrow self-interest, but it can also be an incentive to service to others, as, e.g., in a charitable fund-raising marathon or even a large manufacturing enterprise supplying a needed good to the public. Similarly co-operation may be for the good of all, as socialists assume. But it can also be a means of collusion for purposes of price-fixing and other forms of corruption. Might the American founders have missed this element of human nature in their ostensibly "realistic" view?

Thus it may be that the expanding power of the courts has come with the blessing of the legislative branch. Here's Budziszewski again:

Another fact bolstering Brutus's case is that whereas federal legislators periodically face the electorate, federal judges don't. This makes Congress much more risk-averse than courts are. Rather than resenting the judiciary for taking hot-button issues out of its hands, the legislature may be relieved and grateful that someone else has made the decision for them (p. 153).

This is a conclusion I came to some time ago with respect to Canada. Since 1982 our courts have been making decisions that are increasingly imaginative and even in open conflict with the intentions of the drafters of the Constitution Act, 1982. We know this because, unlike the American founders, most of the players in the patriation drama are still very much alive! Given our convention of responsible government, a sitting government is reluctant to make decisions of a controversial nature. It is easier to leave such decisions up to the courts, who do not have to face the people. The Supreme Court's Reference re Québec secession is in many respects an ingenious decision that gave something to both sides and helped to prop up the federalist cause in Québec. Nevertheless, one would be hard put to demonstrate that the ruling was based on a close reading of our Constitution Acts, which nowhere mention secession.

Here in Canada we have Section 33, the Notwithstanding Clause, that legislators can invoke to override judicial decisions based on Sections 2 and 7-15 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Yet over the past quarter century few legislatures, with the exception of Québec's National Assembly, have been willing to invoke it. I believe Budziszewski, drawing on Brutus, has now given us a credible explanation for this reluctance.

Incidentally, the copy of The Federalist shown above is from my personal library. It is a rebound edition dating from 1818, when two of the authors, James Madison and John Jay, were still alive.

01 June 2008

Sermon posted

For those unable to make either of the worship services at St. John's Church, I have posted this morning's sermon here: Noah's Place in the Redemptive Story.

For those unable to make either of the worship services at St. John's Church, I have posted this morning's sermon here: Noah's Place in the Redemptive Story.