The Pope was wrong

What better way to demonstrate to Benedict XVI that Islam is not, after all, a religion of violence: Greek Orthodox Church Attacked With Pipe Bombs In Gaza.

28 September 2006

Baptists becoming Reformed?

More than two decades ago, while living in South Bend, Indiana, a young couple showed up at the South Bend Christian Reformed Church, of which I was a member, insisting that they were "Reformed Baptists." They had decided to worship at SBCRC, because its Reformed confessional stance outweighed for them their differences in understanding the sacraments. They brought with them numerous stories of fellow Baptists who were converted to Calvinism. I recall expressing puzzlement as to which element of Calvin's teachings had worked such a change in these Christians. Their response? TULIP.

This attachment to the doctrines represented by the famous floral acronym seems also to be behind the stories recounted here: Young, Restless, Reformed. It should be noted that virtually everyone in these stories is a Baptist of some sort. Given this fact, three groups of questions would appear to merit consideration.

(1) If so many Baptists, especially in the Southern Baptist Convention, are coming to embrace Reformed Christianity, will they not eventually have to confront — and perhaps even embrace — Calvin's teachings on the sacraments and ecclesiology, from which they still evidently dissent? If salvation comes, not from our decision for Christ, but from his choosing us, then wouldn't it be more appropriate to adopt a view of baptism as a sign of God's grace rather than one reflecting a voluntary profession of belief?

(2) The early Reformers recovered the Psalms in the liturgy and commissioned poets and musicians to render them in a form easily singable by an ordinary congregation. Why then does the article fail to mention an increased appreciation for and use of the Psalms in public worship? Has this not been part of the experience of these converts? If not, why not?

(3) Will these Reformed Baptists not also have to think through, along with Abraham Kuyper, the implications of God's sovereignty for every area of life? Will they come to have an appreciation for the larger implications of the cultural mandate (Genesis 1:28)? Or is this ostensibly "enlarged view of God's authority" applicable only to "evangelism, worship, and relationships"?

I suppose I'm ultimately asking this: As these Baptists become more Reformed, will they eventually cease to be Baptist in any meaningful sense? That, of course, cannot be predicted in advance. However, what appears to be lacking in these zealous converts is a sense of the catholicity of the church and of the faith. We do not yet see in them an enlarged sense of the body of Christ, which might make for a more ecumenical emphasis. Nor do they appear to recognize that the church did not disappear between the 1st and 16th centuries. They have adopted a narrowly theological approach to Calvin's teachings, without, as far as I can tell, having a real burden for the institutional church, the sacraments, and a world and life view that touches, well, the whole world and all of life.

More than two decades ago, while living in South Bend, Indiana, a young couple showed up at the South Bend Christian Reformed Church, of which I was a member, insisting that they were "Reformed Baptists." They had decided to worship at SBCRC, because its Reformed confessional stance outweighed for them their differences in understanding the sacraments. They brought with them numerous stories of fellow Baptists who were converted to Calvinism. I recall expressing puzzlement as to which element of Calvin's teachings had worked such a change in these Christians. Their response? TULIP.

This attachment to the doctrines represented by the famous floral acronym seems also to be behind the stories recounted here: Young, Restless, Reformed. It should be noted that virtually everyone in these stories is a Baptist of some sort. Given this fact, three groups of questions would appear to merit consideration.

(1) If so many Baptists, especially in the Southern Baptist Convention, are coming to embrace Reformed Christianity, will they not eventually have to confront — and perhaps even embrace — Calvin's teachings on the sacraments and ecclesiology, from which they still evidently dissent? If salvation comes, not from our decision for Christ, but from his choosing us, then wouldn't it be more appropriate to adopt a view of baptism as a sign of God's grace rather than one reflecting a voluntary profession of belief?

(2) The early Reformers recovered the Psalms in the liturgy and commissioned poets and musicians to render them in a form easily singable by an ordinary congregation. Why then does the article fail to mention an increased appreciation for and use of the Psalms in public worship? Has this not been part of the experience of these converts? If not, why not?

(3) Will these Reformed Baptists not also have to think through, along with Abraham Kuyper, the implications of God's sovereignty for every area of life? Will they come to have an appreciation for the larger implications of the cultural mandate (Genesis 1:28)? Or is this ostensibly "enlarged view of God's authority" applicable only to "evangelism, worship, and relationships"?

I suppose I'm ultimately asking this: As these Baptists become more Reformed, will they eventually cease to be Baptist in any meaningful sense? That, of course, cannot be predicted in advance. However, what appears to be lacking in these zealous converts is a sense of the catholicity of the church and of the faith. We do not yet see in them an enlarged sense of the body of Christ, which might make for a more ecumenical emphasis. Nor do they appear to recognize that the church did not disappear between the 1st and 16th centuries. They have adopted a narrowly theological approach to Calvin's teachings, without, as far as I can tell, having a real burden for the institutional church, the sacraments, and a world and life view that touches, well, the whole world and all of life.

25 September 2006

A Tory on fraternity

Hegel's ideas are alive and well in the person of Danny Kruger, who applies the German philosopher's dialectic to British politics in The right dialectic. Kruger argues that the revolutionary triad of liberty, equality and fraternity well represents the ongoing quarrel between left and right, with the former focussing on equality and the latter on liberty. Both groups value fraternity, even if they interpret it differently. At base it is

Kruger's essay is helpful in giving us a sense of the direction of the Conservative Party under its current leader David Cameron. What Kruger appears to misunderstand is the origin of the terms left and right in the horseshoe-shaped parliaments he erroneously views as attempts to overcome them. They certainly did not originate at Westminster, as he seems to imply.

Thanks to Paul Bowman for alerting us to this article. Bowman has asked me whether Kruger's musings represent a movement within the Conservative Party in a christian democratic direction. Possibly, but these ideas are by no means new within the Party. Former leader William Hague (who bears an uncanny resemblance to Kelsey Grammer of Frasier fame) set them forth in a speech titled, "Identity and the British Way," since removed from the Conservative Party website but which I mention in my book.

Hegel's ideas are alive and well in the person of Danny Kruger, who applies the German philosopher's dialectic to British politics in The right dialectic. Kruger argues that the revolutionary triad of liberty, equality and fraternity well represents the ongoing quarrel between left and right, with the former focussing on equality and the latter on liberty. Both groups value fraternity, even if they interpret it differently. At base it is

the sphere of belonging, of membership, the sphere of identity and particularity. It exists in civil society, in the arena of commercial and social enterprise, of family and nation. It concerns neighbourhood, voluntary association, faith, and all the other elements of identity that relate us to some and distinguish us from others. It concerns culture.

Kruger's essay is helpful in giving us a sense of the direction of the Conservative Party under its current leader David Cameron. What Kruger appears to misunderstand is the origin of the terms left and right in the horseshoe-shaped parliaments he erroneously views as attempts to overcome them. They certainly did not originate at Westminster, as he seems to imply.

Thanks to Paul Bowman for alerting us to this article. Bowman has asked me whether Kruger's musings represent a movement within the Conservative Party in a christian democratic direction. Possibly, but these ideas are by no means new within the Party. Former leader William Hague (who bears an uncanny resemblance to Kelsey Grammer of Frasier fame) set them forth in a speech titled, "Identity and the British Way," since removed from the Conservative Party website but which I mention in my book.

24 September 2006

Church notes

This morning our family was privileged to attend Divine Liturgy at All Saints of North America Orthodox Church in Hamilton's east end, courtesy of our friend, John Loukidelis, a reader of this blog. The congregation is quite small, but extremely friendly. Thanks are due them for their generous hospitality. The Priest-in-Charge, Fr. Geoffrey Korz, preached a sermon urging his hearers to recognize that love of God is not just something to be cordoned off from daily living but must extend to the whole of life.

On another note, the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, in Berry Pomeroy, Devon, England, sang one of my versifications of Psalm 95 at Morning Prayer today. It will be sung again at the 11.15 am service on sunday, 23 October. I'd love to be there myself to hear it. I understand that the St. Mary's building was the setting for the final wedding scene in Ang Lee's cinematic version of Sense and Sensibility.

This morning our family was privileged to attend Divine Liturgy at All Saints of North America Orthodox Church in Hamilton's east end, courtesy of our friend, John Loukidelis, a reader of this blog. The congregation is quite small, but extremely friendly. Thanks are due them for their generous hospitality. The Priest-in-Charge, Fr. Geoffrey Korz, preached a sermon urging his hearers to recognize that love of God is not just something to be cordoned off from daily living but must extend to the whole of life.

On another note, the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, in Berry Pomeroy, Devon, England, sang one of my versifications of Psalm 95 at Morning Prayer today. It will be sung again at the 11.15 am service on sunday, 23 October. I'd love to be there myself to hear it. I understand that the St. Mary's building was the setting for the final wedding scene in Ang Lee's cinematic version of Sense and Sensibility.

22 September 2006

God and the welfare state

Remember Lew Daly's Compassion Capital, on which I blogged here? Well, now it's in book form, titled God and the Welfare State, to be released next month. Daly has offered to have a copy sent to me by the publisher once it's out. I look forward to reading it.

Remember Lew Daly's Compassion Capital, on which I blogged here? Well, now it's in book form, titled God and the Welfare State, to be released next month. Daly has offered to have a copy sent to me by the publisher once it's out. I look forward to reading it.

What? No more ad hominem?

Can it be true? The New Pantagruel is closing shop. And so soon after this. I don't think we're in Kansas anymore, Toto.

Can it be true? The New Pantagruel is closing shop. And so soon after this. I don't think we're in Kansas anymore, Toto.

21 September 2006

Artificial happiness?

I must admit to being ambivalent about Richard John Neuhaus' comments on Ronald Dworkin's Artificial Happiness: The Dark Side of the New Happy Class. Although I usually agree more than I disagree with Neuhaus — at least on specific issues — in this case I fear he is labouring under a misunderstanding of the nature of the illnesses that prompt people to take antidepressants such as Prozac or Zoloft. Though I've not read the book at issue, I suspect that neither Dworkin nor Neuhaus has ever suffered from depression, which is considerably more than just unhappiness. When properly used, these medications help to free the mind, not just from unhappiness, but from anxieties gone into overdrive, which can adversely affect how one approaches one's work, relates to other people, and views past and future.

I find myself wondering whether Dworkin and Neuhaus would make the same judgements on people suffering from, say, diabetes or hypothyroidism who need insulin or a hormone supplement to keep themselves alive and functioning. Or even those who take Tylenol for a headache. Are these people to be labelled artificially healthy or pain-free? We all know, of course, that pain helps to alert us to potentially deeper health issues needing attention, and a painkiller may lull us into ignoring the root causes of a malady. I have no doubt that psychoactive medications can be abused. They certainly should not be used to make "people feel good about their disordered selves and their disordered lives." (However, I'm not sure they are even capable of this — of soothing the consciences of people unhappy with their own sins. I doubt any medication can do so.) Yet I believe we are justified in thanking God for the medications that have been developed over the decades to ease pain and cure illness. This includes psychoactive drugs.

I must admit to being ambivalent about Richard John Neuhaus' comments on Ronald Dworkin's Artificial Happiness: The Dark Side of the New Happy Class. Although I usually agree more than I disagree with Neuhaus — at least on specific issues — in this case I fear he is labouring under a misunderstanding of the nature of the illnesses that prompt people to take antidepressants such as Prozac or Zoloft. Though I've not read the book at issue, I suspect that neither Dworkin nor Neuhaus has ever suffered from depression, which is considerably more than just unhappiness. When properly used, these medications help to free the mind, not just from unhappiness, but from anxieties gone into overdrive, which can adversely affect how one approaches one's work, relates to other people, and views past and future.

I find myself wondering whether Dworkin and Neuhaus would make the same judgements on people suffering from, say, diabetes or hypothyroidism who need insulin or a hormone supplement to keep themselves alive and functioning. Or even those who take Tylenol for a headache. Are these people to be labelled artificially healthy or pain-free? We all know, of course, that pain helps to alert us to potentially deeper health issues needing attention, and a painkiller may lull us into ignoring the root causes of a malady. I have no doubt that psychoactive medications can be abused. They certainly should not be used to make "people feel good about their disordered selves and their disordered lives." (However, I'm not sure they are even capable of this — of soothing the consciences of people unhappy with their own sins. I doubt any medication can do so.) Yet I believe we are justified in thanking God for the medications that have been developed over the decades to ease pain and cure illness. This includes psychoactive drugs.

18 September 2006

Architecture

From ages 6 to 14 I aspired to become an architect. As a child I used to spend hours drawing floor plans of homes, fancying myself the heir of the great Frank Lloyd Wright, who once lived in the city of my birth, Oak Park, Illinois. Taking a drafting course in high school convinced me that architecture was not for me after all. Nevertheless, I still have an interest in the subject. When my niece married a Chicago architect a few months ago, he and I discovered we had much to talk about. Moreover, when some friends visited my home many years ago, they noticed that much of the art on my walls consisted of cityscapes and buildings. I hadn't put two and two together before that, but I realized then that I still care about the buildings where we live our lives from day to day. A week ago last friday Comment published a thoughtful article by David Greusel, Why architecture matters. It's a great piece and I can easily resonate with the concerns expressed therein.

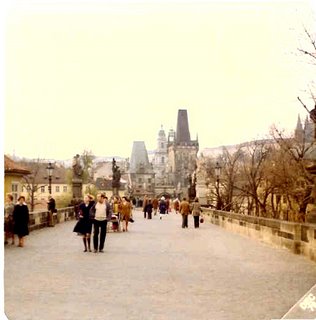

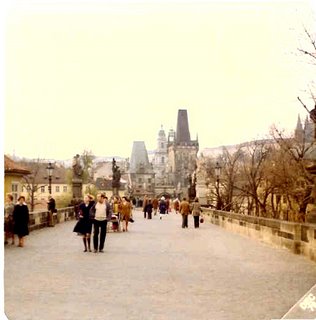

In late 1976 I visited Prague (right), the capital of what was then still called Czechoslovakia. Immediately I fell in love with this perfect jewel of a city, with many of its buildings dating back to the 14th century when the Emperor Charles IV made it his capital. Because it was spared the destruction of the two world wars, it still retained its character — at least at its centre. Of course, three decades ago the country was under the communists, whose rule affected the architecture constructed between 1948 and 1989. Prague thus offered a fascinating contrast within its own borders. On the one hand was the old city, constructed in grand style befitting the seat of an emperor.

On the other hand, the periphery of the city suffered from the blight of a dour stalinist architectural style imported from the Soviet Union. For communists any human touches to our homes, schools, workplaces and public buildings are deemed remnants of a decadent capitalism, to be replaced eventually by a sternly proletarian functionalism divorced from the realities of human communities and the relationships nurtured therein.

We can be grateful that the communists saw fit to retain the late mediaeval heart of Prague, rather than effacing it altogether as they did the former East Prussian city of Königsberg, now known as Kaliningrad. This suggests that, despite the depredations of a destructive worldview, the rulers of Czechoslovakia recognized the treasures they had inherited from their precommunist predecessors and rightly sought to preserve them for future generations.

Yet there are places in the noncommunist western world where the architectural legacy of previous generations is too easily cast aside when economic imperatives dictate. For example, my home city of Chicago (above left in 1976) boasts some of the best known cutting-edge architecture in the world. However, in my personal library I have a nostalgic volume titled, Lost Chicago, by David Lowe, filled with more than 200 pages of photographs telling the sad story of a city's vanished heritage. Of course, some of this perished in the Great Fire of 1871, but most of it was deliberately destroyed to make way for something newer and ostensibly better.

Back in 1984, when the decision was made to demolish the old Chicago & Northwestern terminal on Madison and Canal Streets, and build in its place a metal and glass skyscraper to be called the Northwestern Atrium Center, I wrote a letter of protest to the Chicago Tribune, subsequently published in the 23 June issue of that year. Here is the letter, with which, apart from a few rhetorical flourishes, I still agree:

More than two decades later, as I look back on what I wrote then, it occurs to me that we need to address an important question: Given that we cannot and should not save every building that has ever been constructed, what criteria should we use to decide which to preserve and which to replace? I'd love to hear some discussion of this.

From ages 6 to 14 I aspired to become an architect. As a child I used to spend hours drawing floor plans of homes, fancying myself the heir of the great Frank Lloyd Wright, who once lived in the city of my birth, Oak Park, Illinois. Taking a drafting course in high school convinced me that architecture was not for me after all. Nevertheless, I still have an interest in the subject. When my niece married a Chicago architect a few months ago, he and I discovered we had much to talk about. Moreover, when some friends visited my home many years ago, they noticed that much of the art on my walls consisted of cityscapes and buildings. I hadn't put two and two together before that, but I realized then that I still care about the buildings where we live our lives from day to day. A week ago last friday Comment published a thoughtful article by David Greusel, Why architecture matters. It's a great piece and I can easily resonate with the concerns expressed therein.

In late 1976 I visited Prague (right), the capital of what was then still called Czechoslovakia. Immediately I fell in love with this perfect jewel of a city, with many of its buildings dating back to the 14th century when the Emperor Charles IV made it his capital. Because it was spared the destruction of the two world wars, it still retained its character — at least at its centre. Of course, three decades ago the country was under the communists, whose rule affected the architecture constructed between 1948 and 1989. Prague thus offered a fascinating contrast within its own borders. On the one hand was the old city, constructed in grand style befitting the seat of an emperor.

On the other hand, the periphery of the city suffered from the blight of a dour stalinist architectural style imported from the Soviet Union. For communists any human touches to our homes, schools, workplaces and public buildings are deemed remnants of a decadent capitalism, to be replaced eventually by a sternly proletarian functionalism divorced from the realities of human communities and the relationships nurtured therein.

We can be grateful that the communists saw fit to retain the late mediaeval heart of Prague, rather than effacing it altogether as they did the former East Prussian city of Königsberg, now known as Kaliningrad. This suggests that, despite the depredations of a destructive worldview, the rulers of Czechoslovakia recognized the treasures they had inherited from their precommunist predecessors and rightly sought to preserve them for future generations.

Yet there are places in the noncommunist western world where the architectural legacy of previous generations is too easily cast aside when economic imperatives dictate. For example, my home city of Chicago (above left in 1976) boasts some of the best known cutting-edge architecture in the world. However, in my personal library I have a nostalgic volume titled, Lost Chicago, by David Lowe, filled with more than 200 pages of photographs telling the sad story of a city's vanished heritage. Of course, some of this perished in the Great Fire of 1871, but most of it was deliberately destroyed to make way for something newer and ostensibly better.

Back in 1984, when the decision was made to demolish the old Chicago & Northwestern terminal on Madison and Canal Streets, and build in its place a metal and glass skyscraper to be called the Northwestern Atrium Center, I wrote a letter of protest to the Chicago Tribune, subsequently published in the 23 June issue of that year. Here is the letter, with which, apart from a few rhetorical flourishes, I still agree:

It saddens me to see the stately old Chicago & Northwestern terminal about to be demolished. To try to soften the blow, the railroad has put up signs and banners cheerily proclaiming, "We're on our way up," meaning, of course, that where the old station now stands will soon be erected yet another of those characterless glass office buildings with an enclosed shopping court at its base. One more link with the city's past will have been sacrificed barbarously at the altar of progress and the almighty dollar.

Chicago is rather like a vain movie star, afraid to let the world see the signs of its age and refusing to grow old gracefully. Every generation the city seems compelled to undergo a facelift, allowing itself to live on an illusion of perpetual youth while eradicating any continuity with its own past. Not every building should be preserved merely because it is old, of course, but the reckless compulsion to destroy and rebuild is not healthy either. Not only has such a city lost touch with its own soul, but it is hardly acting as a fit caretaker and steward of the valuable resources and treasures bequeathed by past generations. When will Chicago learn to value its own heritage instead of glorifying its rootlessness?

More than two decades later, as I look back on what I wrote then, it occurs to me that we need to address an important question: Given that we cannot and should not save every building that has ever been constructed, what criteria should we use to decide which to preserve and which to replace? I'd love to hear some discussion of this.

17 September 2006

At the edge of the solar system

It's official: Dwarf planet gets new name. The distant world temporarily nicknamed "Xena" is now called Eris, after the Greek goddess of discord. In the meantime Pluto has been further downgraded by being assigned a number: 134340. I guess Pluto and Eris can keep each other company out there in theKuyper Kuiper Belt.

It's official: Dwarf planet gets new name. The distant world temporarily nicknamed "Xena" is now called Eris, after the Greek goddess of discord. In the meantime Pluto has been further downgraded by being assigned a number: 134340. I guess Pluto and Eris can keep each other company out there in the

Reaction to Pope's speech

Pope Benedict XVI was unwise to quote Byzantine Emperor Manoel II Palaeologos, who had the temerity to criticize efforts to spread faith at the point of a sword. Just because Constantinople was at the time under siege by the Ottoman Turks was no excuse for the Emperor to let his prejudices get the better of him. As for the Pope, he should definitely make a clearer apology.

Pope Benedict XVI was unwise to quote Byzantine Emperor Manoel II Palaeologos, who had the temerity to criticize efforts to spread faith at the point of a sword. Just because Constantinople was at the time under siege by the Ottoman Turks was no excuse for the Emperor to let his prejudices get the better of him. As for the Pope, he should definitely make a clearer apology.

Marketing the church

What happens when worship becomes a mere tool for evangelism and outreach? Fr. John Parker takes a hard-hitting look at efforts to market the church in Guide for the Cineplexed. Writes Parker:

What happens when worship becomes a mere tool for evangelism and outreach? Fr. John Parker takes a hard-hitting look at efforts to market the church in Guide for the Cineplexed. Writes Parker:

The marketed church offers just what everyone wants: the music I want (or don’t), the time I want, the length of service I want, the type of language I want, the style of music I want, the amount of intimacy and responsibility I want, and in some cases, even the pastor I want. But is the gospel a message about the satisfaction of wants?

The marketed church confuses Sunday worship and catechism with evangelism and outreach. What is the difference? Mere Christian Sunday worship has always been for the Christian community (the baptized) to offer thanks to God, to sing his praise, and to feed on the Word. Evangelism has been done by conversation in the marketplace, preaching in the public square, but even more, simply by the witness of increasingly holy lives.

14 September 2006

Marshall on evangelical activism

My friend Paul Marshall has an article worth reading in this month's Christianity Today: The Problem with Prophets. I would love to see him develop his thoughts further in a longer essay or even a book on the subject.

My friend Paul Marshall has an article worth reading in this month's Christianity Today: The Problem with Prophets. I would love to see him develop his thoughts further in a longer essay or even a book on the subject.

12 September 2006

Lessons from the Antipodes

Do we Canucks have something to learn from the Aussies? Mark Steyn clearly thinks so.

Do we Canucks have something to learn from the Aussies? Mark Steyn clearly thinks so.

A word to the wise

If any of my students dares to wear something made of this material in the classroom, I will make them take it off then and there.

If any of my students dares to wear something made of this material in the classroom, I will make them take it off then and there.

11 September 2006

10 September 2006

Crossing the Tiber

Prof. Ian Hunter, who has spoken at Redeemer in the past, has left the Anglican Church for Rome. My question for him is: why not Constantinople?

Prof. Ian Hunter, who has spoken at Redeemer in the past, has left the Anglican Church for Rome. My question for him is: why not Constantinople?

A budding musician in our household?

Is it unusual for a 7-year-old to be humming Dave Brubeck's Blue Rondo à la Turk and Take Five at the breakfast table? The remarkable thing is that I was easily able to recognize them.

Here is my own homage to Brubeck, titled Rondo Rouge à la Grec (© 2002 David T. Koyzis).

Is it unusual for a 7-year-old to be humming Dave Brubeck's Blue Rondo à la Turk and Take Five at the breakfast table? The remarkable thing is that I was easily able to recognize them.

Here is my own homage to Brubeck, titled Rondo Rouge à la Grec (© 2002 David T. Koyzis).

08 September 2006

Gilead

Last week I read Marilynne Robinson's Pulitzer Prize winning Gilead on the recommendation of a friend. Gilead is a small town in western Iowa, just over the border from Kansas. (In reality, of course, Iowa does not share a border with Kansas, but this geographical fiction is no less plausible than Gilead itself.) Not a conventional novel with a clear plotline and an obvious ending, it instead takes the form of a journal kept by a dying minister of the gospel written for his 7-year-old son whom he will not live to see grow up.

The Rev. John Ames is the third generation of men by that name to have pastored the local Congregational church. Born two decades before the end of the 19th century, he is married briefly in the first years of the 20th. Alas his first wife dies in childbirth, as does the infant daughter. Only when he is in his 60s does he remarry a woman much younger than he and, as he approaches his three-score-years-and-ten, experience the unexpected grace of fatherhood once again.

The beauty of the book lies not in its plot, but in the portrayal of its characters. Robinson flawlessly assumes the voice of an elderly man, persuading the reader that, among other things, the writer really did accompany his father on a journey to Kansas in 1892 to find his grandfather's grave. The most complex character is his namesake, John Ames "Jack" Boughton, the son of his lifelong friend, "old Boughton." Having disgraced the family in his youth and moved away from Gilead, he has now returned to town 20 years later, with unknown motives. Ames fears Jack's influence on his wife and son after he has passed on. Much of the latter part of the book finds him preoccupied with Jack's sudden and unnerving presence in his family's life and his interior struggle over whether he should warn his wife about him.

Oddly enough, however, Ames' second wife, Lila, along with the other women in the book, is not as vivid a character as one would expect from a husband's diary. It may not be fair to call her one-dimensional, yet we know little of her motives and what makes her tick. That's the one thing that does not ring true in an otherwise compelling narrative. On the other hand, given that it is written for his son, who when he reads it will already have known his own mother, Ames might well deem it unnecessary to delve too deeply into her character for his benefit.

There is much to love in this book.

First, although I have never lived in a small town, I was taken with the setting and the relationships nurtured by it. Imagine living in one place one's whole life and enjoying the proximity of lifelong friendships. In a mobile society friendships are generally cultivated for a time and then have to be maintained in attenuated form over a distance as someone moves away. (I have never entirely reconciled myself to this fact of contemporary life.) But Ames and old Boughton — best friends from childhood — grow old together and seemingly face death at nearly the same moment.

Second, I was moved by the father-son relationships portrayed. With remarkable insight, Robinson accurately depicts the love and loyalty, as well as the tensions and conflict, between the generations of a family. Again this rings true.

Finally, Robinson perceptively explores the unfathomable mystery of divine election in the lives of her characters, especially the wayward Jack and Ames' disbelieving brother Edward. Why does God's grace seem to bypass those who, try as they might, cannot bring themselves to believe? Why do others, such as Lila, come to the faith in so ordinary a fashion after sitting through successive weeks of less-than-riveting sermons? The author asks and considers these questions but wisely refrains from trying to answer them.

Robinson's last (and first) novel, Housekeeping, was written a quarter of a century ago. Let's hope she doesn't wait as long to publish a third.

06 September 2006

What if they gave a world and nobody came?

Given the already falling birthrate in Europe, this award-winning advertisement from Belgium would seem to be counterproductive, even from a marketing standpoint. After all, if everyone took its message seriously there would be no one left in another 25 years to purchase the featured product.

Given the already falling birthrate in Europe, this award-winning advertisement from Belgium would seem to be counterproductive, even from a marketing standpoint. After all, if everyone took its message seriously there would be no one left in another 25 years to purchase the featured product.

The europeanization of American politics?

Is the political debate in the United States taking on the character of post-revolutionary politics in 19th- and 20th-century Europe with the two major parties polarizing along religious lines? Joseph Bottum considers this possibility and is most uncomfortable with it:

Although I am to some extent sympathetic with Bottum's skin-crawling reaction, I doubt that his protest will win out at the end of the day. As for American exceptionalism, it is certainly true that the settlements that would form the United States at the end of the 18th century were largely spared the political turbulence that plagued the old continent between 1789 and 1815, with the partial exception of the last three years of this period. The American colonies were in many cases founded by devout Christians seeking the freedom to follow their ultimate beliefs.

That said, during the so-called founding era between 1776 and 1800, the political élites were largely nominal Christians at best, imbued with Enlightenment ideals and holding to a vague deism. Thomas Jefferson was the paradigmatic figure of this period. However, at the turn of the new century a series of religious revivals swept through the new republic, significantly altering the face of its public life. After this point evangelical protestantism dominated the expanding nation up until the cultural changes following the Great War.

What makes the United States exceptional, then, is not so much the bundle of ideals said to constitute the American enterprise; it is rather the historic vacillation between the dominance of christian and secular forces, with one in the ascendancy at one time and the other temporarily supplanting it. This is in contrast to Europe where the long range trend has been in one direction: secularization. Is the US finally conforming to this European pattern?

Having been born and brought up in the US, my own sense is that the larger trend, at least at present, is towards a more overt public presence of the traditionally religious. Jimmy Carter was the first presidential candidate to label himself openly as a "born-again Christian" back in 1976. Prior to that time, explicit claims to a particular confessional identity were all but unknown amongst national political leaders. Since that time, such claims appear almost to be the rule rather than the exception. That such claims find a home more naturally within the Republican than the Democratic Party goes some way in explaining the former's dominance in recent years.

That said, the Republican Party is far from being a European-style christian democratic party, especially considering the presence within its fold of libertarians and free-marketeers. President Bush's "compassionate conservatism" marks, at least in part, a departure from this anti-government support base. But this hardly guarantees the GOP's transformation into a christian democratic party. If anything, Bush, with the best of intentions, has engaged in dangerous overreach, overestimating the power of government in general and the US government in particular, much as Lyndon Johnson did four decades ago.

This suggests to me that, after Bush's departure in 2009, the libertarians may once again find themselves in the ascendancy within their party, as Americans react against the "big-government" conservatism of the younger Bush. This could give the Democrats a window of opportunity, if they are willing to abandon their stance on abortion and reach out to the followers of traditional Christianity and Judaism. If they are not, then the Republicans will likely remain dominant, with frustrated evangelicals and Catholics having no choice but to remain within a party where their influence is less than what it once was but more than in the opposing party. Of course, this may be a blessing in disguise as it could force Christians to grapple with the larger issue of formulating a coherent political philosophy rather than settling for a piecemeal gut response to issues such as abortion, marriage and the like.

What about Canada? That's for a future post.

Is the political debate in the United States taking on the character of post-revolutionary politics in 19th- and 20th-century Europe with the two major parties polarizing along religious lines? Joseph Bottum considers this possibility and is most uncomfortable with it:

I wrote, as though it were perfectly self-evident, “We cannot—we should not—have a party so strongly identified with opposition to religious believers.” And a Europeanized friend emailed to call me on my over-easy assumption: “Why shouldn’t we have one party that is friendly to religion and one unfriendly? That is the pattern in most developed countries, and surely, as the Republican party increasingly takes on the attributes of a European-style Christian Democratic party, it is logical that their opponents take the other position.”

The attribution of cause here is a little one-sided, as though the poor liberals were forced into their un- and anti-religious positions entirely by the conservatives’ donning of the religious mantle. Even the good Democrat Amy Sullivan blames some of this on the way the Democratic party has behaved. Still, my friend’s general point is a good one: The First World pattern has been a Social Democratic party versus a Christian Democratic party, an anti-religious party versus a religious party, and if politics in the United States is starting to match that pattern, why is this surprising or undesirable?

My first answer was that the idea makes my skin crawl—which is just another way of saying I had been assuming that American exceptionalism lets us sidestep this whole wars-of-religion, Westphalia, philosophes, French Revolution, last-king-strangled-with-the-guts-of-the-last-priest European thing.

In a way, I still think that my original assumption is the answer. A developed argument about American exceptionalism and the nature of the American Founding would take us a long way toward understanding why we don’t want religion to be pushed from the shared mainstream over to one side’s shore.

Although I am to some extent sympathetic with Bottum's skin-crawling reaction, I doubt that his protest will win out at the end of the day. As for American exceptionalism, it is certainly true that the settlements that would form the United States at the end of the 18th century were largely spared the political turbulence that plagued the old continent between 1789 and 1815, with the partial exception of the last three years of this period. The American colonies were in many cases founded by devout Christians seeking the freedom to follow their ultimate beliefs.

That said, during the so-called founding era between 1776 and 1800, the political élites were largely nominal Christians at best, imbued with Enlightenment ideals and holding to a vague deism. Thomas Jefferson was the paradigmatic figure of this period. However, at the turn of the new century a series of religious revivals swept through the new republic, significantly altering the face of its public life. After this point evangelical protestantism dominated the expanding nation up until the cultural changes following the Great War.

What makes the United States exceptional, then, is not so much the bundle of ideals said to constitute the American enterprise; it is rather the historic vacillation between the dominance of christian and secular forces, with one in the ascendancy at one time and the other temporarily supplanting it. This is in contrast to Europe where the long range trend has been in one direction: secularization. Is the US finally conforming to this European pattern?

Having been born and brought up in the US, my own sense is that the larger trend, at least at present, is towards a more overt public presence of the traditionally religious. Jimmy Carter was the first presidential candidate to label himself openly as a "born-again Christian" back in 1976. Prior to that time, explicit claims to a particular confessional identity were all but unknown amongst national political leaders. Since that time, such claims appear almost to be the rule rather than the exception. That such claims find a home more naturally within the Republican than the Democratic Party goes some way in explaining the former's dominance in recent years.

That said, the Republican Party is far from being a European-style christian democratic party, especially considering the presence within its fold of libertarians and free-marketeers. President Bush's "compassionate conservatism" marks, at least in part, a departure from this anti-government support base. But this hardly guarantees the GOP's transformation into a christian democratic party. If anything, Bush, with the best of intentions, has engaged in dangerous overreach, overestimating the power of government in general and the US government in particular, much as Lyndon Johnson did four decades ago.

This suggests to me that, after Bush's departure in 2009, the libertarians may once again find themselves in the ascendancy within their party, as Americans react against the "big-government" conservatism of the younger Bush. This could give the Democrats a window of opportunity, if they are willing to abandon their stance on abortion and reach out to the followers of traditional Christianity and Judaism. If they are not, then the Republicans will likely remain dominant, with frustrated evangelicals and Catholics having no choice but to remain within a party where their influence is less than what it once was but more than in the opposing party. Of course, this may be a blessing in disguise as it could force Christians to grapple with the larger issue of formulating a coherent political philosophy rather than settling for a piecemeal gut response to issues such as abortion, marriage and the like.

What about Canada? That's for a future post.

04 September 2006

Warren on 'chestlessness'

Canada's own David Warren is hardly a stranger to controversy. A recent column of his, Chestlessness, has engendered no small amount of discussion in the blogosphere, because in it he excoriates the two captured Fox News journalists who went along with their captors even to the extent of "converting" to Islam. Warren, who is an adult convert to Catholicism, responds to his critics here.

Although I am sympathetic with Warren's critique, I do wonder whether one can realistically expect someone who is not a Christian to display the same courage in the face of martyrdom that so many followers of Jesus Christ have manifested over the centuries. To die for something as abstract as "the West" while lacking an ultimate hope in redemption is almost certainly more than one can demand from a journalist steeped in a secular worldview.

Canada's own David Warren is hardly a stranger to controversy. A recent column of his, Chestlessness, has engendered no small amount of discussion in the blogosphere, because in it he excoriates the two captured Fox News journalists who went along with their captors even to the extent of "converting" to Islam. Warren, who is an adult convert to Catholicism, responds to his critics here.

Although I am sympathetic with Warren's critique, I do wonder whether one can realistically expect someone who is not a Christian to display the same courage in the face of martyrdom that so many followers of Jesus Christ have manifested over the centuries. To die for something as abstract as "the West" while lacking an ultimate hope in redemption is almost certainly more than one can demand from a journalist steeped in a secular worldview.

Confessing 'sin'?

Last week I worshipped at a local Presbyterian church. In the course of the liturgy, the congregation recited a general confession of sin that contained this line: "When we exclude others with our theology, language, traditions, and practices, gracious God, forgive us." This could be interpreted in one of two ways. First: "when we put up unnecessary and unbiblical barriers to fellowship, gracious God, forgive us." Or second: "when we claim that only those in Christ are saved, gracious God, forgive us." I will not attempt to speculate as to which meaning was intended.

Last week I worshipped at a local Presbyterian church. In the course of the liturgy, the congregation recited a general confession of sin that contained this line: "When we exclude others with our theology, language, traditions, and practices, gracious God, forgive us." This could be interpreted in one of two ways. First: "when we put up unnecessary and unbiblical barriers to fellowship, gracious God, forgive us." Or second: "when we claim that only those in Christ are saved, gracious God, forgive us." I will not attempt to speculate as to which meaning was intended.