From ages 6 to 14 I aspired to become an architect. As a child I used to spend hours drawing floor plans of homes, fancying myself the heir of the great Frank Lloyd Wright, who once lived in the city of my birth, Oak Park, Illinois. Taking a drafting course in high school convinced me that architecture was not for me after all. Nevertheless, I still have an interest in the subject. When my niece married a Chicago architect a few months ago, he and I discovered we had much to talk about. Moreover, when some friends visited my home many years ago, they noticed that much of the art on my walls consisted of cityscapes and buildings. I hadn't put two and two together before that, but I realized then that I still care about the buildings where we live our lives from day to day. A week ago last friday Comment published a thoughtful article by David Greusel, Why architecture matters. It's a great piece and I can easily resonate with the concerns expressed therein.

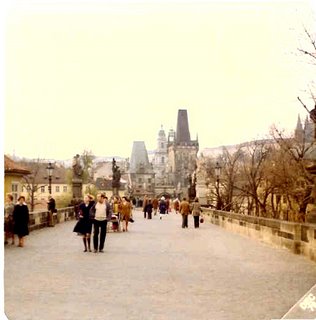

In late 1976 I visited Prague (right), the capital of what was then still called Czechoslovakia. Immediately I fell in love with this perfect jewel of a city, with many of its buildings dating back to the 14th century when the Emperor Charles IV made it his capital. Because it was spared the destruction of the two world wars, it still retained its character — at least at its centre. Of course, three decades ago the country was under the communists, whose rule affected the architecture constructed between 1948 and 1989. Prague thus offered a fascinating contrast within its own borders. On the one hand was the old city, constructed in grand style befitting the seat of an emperor.

On the other hand, the periphery of the city suffered from the blight of a dour stalinist architectural style imported from the Soviet Union. For communists any human touches to our homes, schools, workplaces and public buildings are deemed remnants of a decadent capitalism, to be replaced eventually by a sternly proletarian functionalism divorced from the realities of human communities and the relationships nurtured therein.

We can be grateful that the communists saw fit to retain the late mediaeval heart of Prague, rather than effacing it altogether as they did the former East Prussian city of Königsberg, now known as Kaliningrad. This suggests that, despite the depredations of a destructive worldview, the rulers of Czechoslovakia recognized the treasures they had inherited from their precommunist predecessors and rightly sought to preserve them for future generations.

Yet there are places in the noncommunist western world where the architectural legacy of previous generations is too easily cast aside when economic imperatives dictate. For example, my home city of Chicago (above left in 1976) boasts some of the best known cutting-edge architecture in the world. However, in my personal library I have a nostalgic volume titled, Lost Chicago, by David Lowe, filled with more than 200 pages of photographs telling the sad story of a city's vanished heritage. Of course, some of this perished in the Great Fire of 1871, but most of it was deliberately destroyed to make way for something newer and ostensibly better.

Back in 1984, when the decision was made to demolish the old Chicago & Northwestern terminal on Madison and Canal Streets, and build in its place a metal and glass skyscraper to be called the Northwestern Atrium Center, I wrote a letter of protest to the Chicago Tribune, subsequently published in the 23 June issue of that year. Here is the letter, with which, apart from a few rhetorical flourishes, I still agree:

It saddens me to see the stately old Chicago & Northwestern terminal about to be demolished. To try to soften the blow, the railroad has put up signs and banners cheerily proclaiming, "We're on our way up," meaning, of course, that where the old station now stands will soon be erected yet another of those characterless glass office buildings with an enclosed shopping court at its base. One more link with the city's past will have been sacrificed barbarously at the altar of progress and the almighty dollar.

Chicago is rather like a vain movie star, afraid to let the world see the signs of its age and refusing to grow old gracefully. Every generation the city seems compelled to undergo a facelift, allowing itself to live on an illusion of perpetual youth while eradicating any continuity with its own past. Not every building should be preserved merely because it is old, of course, but the reckless compulsion to destroy and rebuild is not healthy either. Not only has such a city lost touch with its own soul, but it is hardly acting as a fit caretaker and steward of the valuable resources and treasures bequeathed by past generations. When will Chicago learn to value its own heritage instead of glorifying its rootlessness?

More than two decades later, as I look back on what I wrote then, it occurs to me that we need to address an important question: Given that we cannot and should not save every building that has ever been constructed, what criteria should we use to decide which to preserve and which to replace? I'd love to hear some discussion of this.

No comments:

Post a Comment