Unlike Roman Catholicism, which constitutes a single global organization under a spiritual CEO known as the Pope, Orthodox Christianity has always had something of a fractious character. In the old world, the Orthodox are organized into self-governing autocephalous churches covering limited territories, often but not always corresponding to the boundaries of a particular state. All of these churches are united in a single faith, reading a Bible somewhat larger than those of Protestants and Catholics (although Russians and Greeks differ here), and recognizing the Patriarch of Constantinople as Ecumenical Patriarch, the first among equals of the church's hierarchs. Each church is in communion with the others, accepting as normative the decisions of the Seven Ecumenical Councils of the first millennium.

As a result of the missionary activities of the apostles and their successors, the church grew phenomenally in the first centuries, expanding to the borders of the Roman Empire and beyond. Five patriarchs were set over the church, as shown in this map:

The patriarchs of Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem claimed territorial jurisdictions over the Christian world in what became known as the Pentarchy under the Emperor Justinian the Great (482-565). (The Church of Cyprus became autocephalous in 431, no longer under the jurisdiction of Antioch, yet its archbishop was not accorded the title of patriarch. It remains autocephalous to the present day.)

The map above makes this arrangement appear to be a neat territorial division among the patriarchal sees of the church. But the reality was more complicated. In particular, Rome put forward claims of superiority to the other four sees. Furthermore, the boundaries among these provinces were subject to dispute, a tradition, sad to say, that continues within global Orthodoxy.

Communion was broken between Rome and Constantinople more than once during this era, most notably during the Photian schism of the 9th century, but these breaches had always been repaired after some time had passed. The final break came in 1054 when Pope and Ecumenical Patriarch parted ways over issues which by then were dividing east and west, including the filioque clause of the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, which the western church had added without consulting the east. In the immediate aftermath of the break, most Christians, if they were aware of it at all, likely thought it would eventually be healed, as previous breaks had been.

However, in 1204 crusaders from western Europe sacked Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade, looting valuable artefacts, many of which ended up in the hands of the Venetian Republic. Although Pope Innocent III excommunicated the crusaders in the aftermath, this event hardened the division between east and west, which remains to this day, despite 20th-century efforts to facilitate reconciliation.

As a result, the ancient Pentarchy became a Tetrarchy, with Constantinople, Antioch, Alexandria, and Jerusalem in communion with each other, with the first see's bishop, known as the Ecumenical Patriarch, recognized as first among equals despite having one of the smallest churches. Today there are as many as nine patriarchal sees, including Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem, Moscow, Georgia, Serbia, Romania, and Bulgaria. This map indicates the current organization of the church in Europe:

In principle, the Patriarch of Moscow has the largest flock of all, even if actual church attendance does not keep up with the claimed numbers. On this basis, he at least implicitly claims a certain primacy within global Orthodoxy, thereby effectively making himself a rival to the Ecumenical Patriarch. Back to this in a moment.

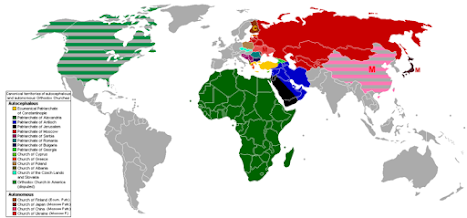

Once we leave the old world, we see that Orthodoxy is even more fragmented, with multiple overlapping jurisdictions following, not territorial, but ethnic lines. We see this in the map below:

In North America in particular there are overlapping Greek, Russian, Romanian, Bulgarian, &c., jurisdictions, plus one autocephalous church in the Orthodox Church in America. If you are an Orthodox Christian moving from, say, New York to Chicago, you will have to decide with which of these Orthodox jurisdictions to affiliate. The fractiousness of Orthodoxy in North America approaches that of Protestantism. I will leave out of this brief survey the various groups not formally in communion with the canonical Orthodox churches.

In 2019 Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew recognized the autocephalous status of a Ukrainian Orthodox Church, as recounted in this article republished by the Encyclopaedia Britannica: Why church conflict in Ukraine reflects historic Russian-Ukrainian tensions. There are in fact two--well, maybe three--Orthodox churches in Ukraine:

The older and larger church is the Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Moscow Patriarchate. According to Ukrainian government statistics, this church had over 12,000 parishes in 2018. A branch of the Russian Orthodox Church, it is under the spiritual authority of Patriarch Kirill of Moscow. Patriarch Kirill and his predecessor, Patriarch Aleksii II, both have repeatedly emphasized the powerful bonds that link the peoples of Ukraine and Russia.

By contrast, the second, newer church, the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, celebrates its independence from Moscow. With the blessing of the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople, a solemn council met in Kyiv in December 2018, created the new church, and elected its leader, Metropolitan Epifaniy. In January 2019, Patriarch Bartholomew formally recognized the Orthodox Church of Ukraine as a separate, independent and equal member of the worldwide communion of Orthodox churches.

Completely self-governing, the Orthodox Church of Ukraine was the culmination of decades of efforts by Ukrainian believers who wanted their own national church, free from any foreign religious authority. As an expression of Ukrainian spiritual independence, this new self-governing Orthodox Church of Ukraine has been a challenge to Moscow. In Orthodox terminology, the Orthodox Church of Ukraine claims autocephaly.

Church schisms occur all the time in various places for various reasons. But few have obvious political ramifications. In the wake of Bartholomew's action, Kirill severed relations with Constantinople, claiming that Turkey's reversion of Hagia Sophia to mosque status was God's punishment for usurping Moscow's canonical rights over Ukraine. The Churches of Greece and Cyprus have also recognized Ukrainian autocephaly, which has prompted Moscow to cut ties with them as well.

So for the moment global Orthodoxy is divided, its potential unity subject to developments in the battlefields of Ukraine. A century and a half separated the Great Schism from the Fourth Crusade. This time only three years separated the Moscow-Constantinople rift from the Russia-Ukraine War of 2022. Time will tell whether the current rift will now harden into a centuries-long schism.

It seems unbelievable that an ecclesiastical schism could be a precursor to actual warfare in the 21st century. We might look back to the religious wars of the 16th century, settled by the Peace of Augsburg in 1555, and the devastating Thirty Years' War of the following century, and conclude that humanity must have outgrown religious warfare.

However, if we accept that the several political ideologies on offer today are rooted in a devout secularism every bit as religious as Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, then we are more likely to see that religious warfare is still with us. With respect to the current Russo-Ukrainian War, what we are seeing is a war of aggression motivated by nationalism and imperialism. That these are rivals of the Christian faith is something that Patriarch Kirill seems determined to overlook as he refuses to discipline the most powerful member of his flock and to put the weight of his office behind the restoration of a just peace. If anything, his silence may push more of his Ukrainian flock into the autocephalous church and out of his jurisdiction. In the meantime, Orthodox fractiousness continues, with no resolution in sight.

For further reading:

- Benz, Ernst. The Eastern Orthodox Church: Its Thought and Life. Garden City, NY: Doubleday/Anchor, 1963.

- Koyzis, David. Imaging God and His Kingdom: Eastern Orthodoxy's Iconic Political Ethic. Review of Politics. Vol. 55, No. 2 (Spring, 1993), pp. 267-289.

- Lossky, Vladimir. The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1976. Originally published 1944.

- Meyendorff, John. Imperial Unity and Christian Divisions. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1989.

- ________. The Orthodox Church: Its Past and Its Role in the World Today. New York: Pantheon Books/Random House, 1962.

- Payton, James R., Jr. Light from the Christian East: An Introduction to the Orthodox Tradition. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 2009.

- Schmemann, Alexander. Historical Road of Eastern Orthodoxy. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1977.

- Ware, Timothy (Kallistos). The Orthodox Church. New Edition. London: Penguin, 1993.

No comments:

Post a Comment