The past year’s celebration of Canada’s 150th birthday reminded me of another anniversary: that of my first visit to this country, which occurred 50 years ago. I was 12 years old, and my father had promised us that we would be seeing Expo 67, the world’s fair in Montréal. We had been expecting this all summer, but school rolled around and we hadn’t yet made the trip. We children knew that the fair would not last forever, and we feared missing it if we waited too long.

October rolled around and still no fair. As Expo would be wrapping up at the end of the month, we got more nervous. But then, on the fifth day of the month, I came home from school to learn that we would be getting in our family’s Buick Electra and leaving for the fair in only two hours! I can no longer recall whether my mother had already packed for all eight of us, but we soon headed off into the night, as prepared as we were ever going to be.

29 December 2017

28 December 2017

What’s in a name? Fundamentalism, evangelicalism and the fickleness of labels

A good friend of mine in graduate school was an ordained minister in

the Presbyterian Church (USA). A confessionally Reformed Christian, he

admitted to me that he sometimes liked to call himself a fundamentalist

just to see how others would respond. Though we were on the same page in

so many ways, I personally didn’t think I could go quite that far.

A good friend of mine in graduate school was an ordained minister in

the Presbyterian Church (USA). A confessionally Reformed Christian, he

admitted to me that he sometimes liked to call himself a fundamentalist

just to see how others would respond. Though we were on the same page in

so many ways, I personally didn’t think I could go quite that far.Nevertheless, I was raised in what might well be regarded as the first fundamentalist denomination, the Orthodox Presbyterian Church. Established in 1936 by John Gresham Machen and others, it grew out of the controversies of the 1920s and ’30s in the former Presbyterian Church in the United States of America. Confessional liberals, who elevated personal experience and rationalism above both the Bible and the Westminster Standards, gradually moved into the ascendancy, with the more conservative elements increasingly on the defensive. These trends had already begun in the post-Civil War era, gaining speed around the turn of the 20th century and achieving dominance after the end of the Great War.

27 December 2017

The Queen's Christmas Message, 2017

Exactly sixty years after the Queen first aired her annual Christmas message on television, the Palace posted this fresh message:

We who have faithfully listened to her broadcasts year after year have noticed that their content is more explicitly christian than in the past, as pointed out in this article from The Guardian: How the Queen – the ‘last Christian monarch’ – has made faith her message. The turn of the millennium appears to have marked the start of this unmistakable trend.

This is how she closed her message two days ago:

God save the Queen! Let us pray that, when the time arrives, her heirs and successors will see fit to continue this emphasis in their own Christmas messages.

We who have faithfully listened to her broadcasts year after year have noticed that their content is more explicitly christian than in the past, as pointed out in this article from The Guardian: How the Queen – the ‘last Christian monarch’ – has made faith her message. The turn of the millennium appears to have marked the start of this unmistakable trend.

To the royal household, it is known as the QXB – the Queen’s Christmas broadcast. To millions of people, it is still an essential feature of Christmas Day. To the Queen, her annual broadcast is the time when she speaks to the nation without the government scripting it. But in recent years, it has also become something else: a declaration of her Christian faith. As Britain has become more secular, the Queen’s messages have followed the opposite trajectory.

This is how she closed her message two days ago:

We remember the birth of Jesus Christ, whose only sanctuary was a stable in Bethlehem. He knew rejection, hardship and persecution. And, yet, it is Jesus Christ's generous love and example which has inspired me through good times and bad. Whatever your own experience is this year, wherever and however you are watching, I wish you a peaceful and very happy Christmas.

God save the Queen! Let us pray that, when the time arrives, her heirs and successors will see fit to continue this emphasis in their own Christmas messages.

Harry Blamires, 1916-2017

Harry Blamires (pronounced BLAMers) was not one of the best known of Christian apologists, overshadowed as he was by the likes of his mentor C. S. Lewis and, among Reformed Christians, Cornelius Van Til. Nevertheless, he was a scholar and theologian of the first rank, and he will be remembered for a single book he published in 1963, The Christian Mind. Because there have been so many books published in recent decades on the subject of a Christian worldview, we may forget that there was a time when the need to think in a distinctively christian way was unfamiliar even to regular church-goers, as it was to me when I was growing up. I acquired my copy back in June 1976 (so I wrote inside the front cover), and underscored those passages that leapt out at me. Blamires makes no mention of Abraham Kuyper, the Dutch polymath and statesman with whom I was becoming acquainted and increasingly sympathetic, but, with some exceptions, I saw them as co-belligerents in the effort to alert believers to the comprehensive sovereignty of God in Christ over the whole of life. Here is a wonderful sample of Blamires' writing:

It may be that the dominant evil of our time is neither the threat of nuclear warfare nor the mechanization of society, but the disintegration of human thought and experience into separate unrelated compartments. For a feature of the diseased condition of modern society is the parcelling out of human faculties—physical, emotional, intellectual, spiritual—into distinct categories, separately exploited, separately catered for. Man is dismembered. In the high incidence of mental disease you can measure something of the cost of this dismemberment. In so far as the Church nurtures the schizophrenic Christian, the Church herself contributes to the very process of dismemberment which it is her specific business to check and counter. For the Church's function is properly to reconstitute the concept and the reality of the full man, faculties and forces blended and united in the service of God. The Church's mission as the continuing vehicle of divine incarnation is precisely that—to build and rebuild the unified Body made and remade in the image of the Father. The mind of man must be won for God (TCM, p. 81).Christianity Today carries an obituary of Blamires here: Died: Harry Blamires, the C. S. Lewis Protégé Who Rediscovered ‘The Christian Mind’. May he rest in peace until the resurrection.

13 November 2017

A troubled anniversary

Next year we observe – perhaps “celebrate” doesn’t entirely fit – the 370th anniversary of the modern state, which is generally said to have resulted from the Treaty of Westphalia that ended the devastating Thirty Years War and reshaped the map of Europe. According to this agreement, the European powers would henceforth accept the principle of state sovereignty, namely, that the state is sovereign within its own territory and exempt from interference from its neighbours. This new international order would replace the messy patchwork of feudal fiefdoms that had lasted for centuries in the western part of the continent.

Since that time we have come to see the state, not as a domain of a particular ruler, but as a community of citizens led by their government. But settling its territorial boundaries has been the tricky part. Where does France end and Germany begin? And what of the German lands where, say, Polish is the majority language? For as long as the modern state has existed there have been quarrels over its jurisdiction. Attempts to settle these quarrels have not always succeeded, with the two world wars of the last century among the most tragic of the failures.

Since that time we have come to see the state, not as a domain of a particular ruler, but as a community of citizens led by their government. But settling its territorial boundaries has been the tricky part. Where does France end and Germany begin? And what of the German lands where, say, Polish is the majority language? For as long as the modern state has existed there have been quarrels over its jurisdiction. Attempts to settle these quarrels have not always succeeded, with the two world wars of the last century among the most tragic of the failures.

One Year of Trump

Nobody expected him to win. He was too boorish and crude. He couldn’t

hold his own in a debate, even as, by his sheer presence, he seemed to

be trying to intimidate his opponent. He thumbed his nose at people he

thought weak and made fun of the handicapped. Far from being a polished

orator like his predecessor, his rhetoric consisted of monosyllabic

words spat out with tremendous ferocity, coupled with monotonously

repetitious outbursts of braggadocio. Read more.

08 November 2017

The Queen would not be amused: Julie Payette’s ill-considered remarks

|

| Governor General Julie Payette |

As one of the

Queen's Canadian subjects, I personally doubt she would approve of

the remarks her freshly-minted representative made last week. Some

months ago Prime Minister Justin Trudeau had advised Her Majesty to

appoint Julie Payette, a former astronaut, to the post of Governor

General, an office which she assumed at the beginning of October. In

a Westminster parliamentary system, the Queen and her representatives

must remain impeccably nonpartisan and avoid even a hint of

partiality. The monarch is the guarantor of the constitution and a

symbol of unity for the entire nation. In her sixty-five years on the

throne, Queen Elizabeth II has discharged her weighty

responsibilities admirably, more than living up to the vow

she took in South Africa on her twenty-first birthday.

Sadly, not all of her representatives have managed to follow her example. Last week, Payette addressed the Canadian Science Policy Conference in Ottawa, and in the course of her speech appeared to belittle her fellow citizens who have the temerity to believe in a transcendent God:

07 November 2017

Commemorating a revolution

Exactly one-hundred years ago, a small cadre of revolutionaries seized power in the then Russian capital city of Petrograd. After the Tsar's abdication earlier in the year, a provisional government had attempted to run the fractious country, unwisely attempting to continue the war against Germany that had brought down the imperial régime. While Soviet film director Sergei Eisenstein would immortalize the storming of the Winter Palace in his famous re-enactment three years later, the actions that brought the Bolsheviks to power were much less dramatic. Nevertheless the long-term consequences of the Revolution would reverberate throughout the twentieth century, leading directly or indirectly to the deaths of scores of millions of people in the interest of implementing a political illusion based on a fundamental misreading of human nature.

On this anniversary we do well to acknowledge that human efforts to reshape the world according to the demands of the gods of the age are not without consequences. In particular, when human beings deny the one true God, they don't cease to believe. They simply redirect their beliefs elsewhere. While there is little to celebrate on this solemn occasion, it is appropriate to remember those who lost their lives to the scourge of Marxism-Leninism in the decades following the Revolution. Господи, помилуй! Lord have mercy!

On this anniversary we do well to acknowledge that human efforts to reshape the world according to the demands of the gods of the age are not without consequences. In particular, when human beings deny the one true God, they don't cease to believe. They simply redirect their beliefs elsewhere. While there is little to celebrate on this solemn occasion, it is appropriate to remember those who lost their lives to the scourge of Marxism-Leninism in the decades following the Revolution. Господи, помилуй! Lord have mercy!

19 October 2017

How Socialism Suppresses Society

Last month I was privileged to visit the Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Wake Forest, North Carolina, where I lectured on "How Socialism Suppresses Society." A video of my lecture has been posted on YouTube with Portuguese subtitles for anyone interested. However, as my delivered lecture was an abbreviated version of the text, I am posting the full text here:

Until last year's presidential election campaign, socialism had long been a nasty word in the American political lexicon. It had been associated with the worst forms of tyranny, especially those of the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China. Thus many of us were surprised to see a certain United States Senator from Vermont gain a dedicated following among especially younger voters while proudly wearing the democratic socialist label. Their elders would have blanched at the prospect of a socialist president, while they themselves manifested no such fear of an ideological vision whose character and history is without doubt unfamiliar to them.

Nevertheless, virtually all western democracies can boast a sizeable socialist party of some sort. Britain has its Labour Party, while Australia has its Labor (minus the “u”) Party. France has its Parti Socialiste, and Germany its Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands. Even my own country of Canada has its New Democratic Party, which, while never having governed at the federal level, has managed at times to form the government in half of the country's ten provinces, including Ontario. The United States had a Socialist Party in the first decades of the twentieth century, under the leadership of Eugene Debs (1855-1926), who famously campaigned for the 1920 election from a jail cell, and the venerable Norman Thomas (1884-1968), a Presbyterian minister who stood six times unsuccessfully for the presidency. But the high water mark for the party came in 1932, after which it lost its support base to Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal. As a consequence, the United States remains virtually the only country lacking a major political party adhering to the principles of socialism.

Defining socialism

What exactly is socialism? Definitions vary widely, of course, and it is probably more accurate to speak of socialisms in the plural. Yet despite the differences, most manifestations of socialism have a number of characteristics in common.

Until last year's presidential election campaign, socialism had long been a nasty word in the American political lexicon. It had been associated with the worst forms of tyranny, especially those of the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China. Thus many of us were surprised to see a certain United States Senator from Vermont gain a dedicated following among especially younger voters while proudly wearing the democratic socialist label. Their elders would have blanched at the prospect of a socialist president, while they themselves manifested no such fear of an ideological vision whose character and history is without doubt unfamiliar to them.

|

| Norman Thomas |

Defining socialism

What exactly is socialism? Definitions vary widely, of course, and it is probably more accurate to speak of socialisms in the plural. Yet despite the differences, most manifestations of socialism have a number of characteristics in common.

17 October 2017

October updates

Here are three updates:

- Last month I was privileged to visit Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Wake Forest, North Carolina, where I spoke on "How Socialism Suppresses Society." My lecture has been posted on YouTube with Portuguese subtitles:

- An article of mine has been published in the Autumn 2017 issue of The Bible in Transmission, of the Bible Society (also known as the British and Foreign Bible Society): Populism in Christian Perspective. An excerpt:

One cannot simply blame political leaders for the direction of an entire culture. George Bernard Shaw was perhaps more realistic in his observation that ‘Democracy is a device that ensures we shall be governed no better than we deserve.’ An overstatement perhaps. Yet it is true that political institutions and leaders alike are conditioned by a complex of cultural assumptions characterising the polity as a whole. A people accustomed to autocracy is very likely to be ruled by autocrats. A nation whose people are corrupt in their daily lives are highly unlikely to be governed by leaders careful to avoid conflict of interest in the conduct of public affairs.

- Finally, I have received word from InterVarsity Press that my first book, Political Visions and Illusions, has been approved for a second revised edition, which I will be working on over the next several months. I will keep everyone updated on its progress and projected date of publication. Thanks to the many readers who have made this book a success over nearly a decade and a half.

25 August 2017

Abraham Kuyper and the Pluralist Claims of the Liberal Project, Part 4: The Kuyperian Alternative

|

| Herman Dooyeweerd |

Everyone now presumably agrees that the execution of heretics handed over by the Inquisition to the civil authorities was not only a very bad idea but fundamentally unjust as well. Nevertheless, the major Reformed confessions of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries charge the civil authorities with the responsibility to “protect the sacred ministry; and thus [to] remove and prevent all idolatry and false worship; that the kingdom of antichrist may be thus destroyed and the kingdom of Christ promoted.” By the beginning of the nineteenth century, this confessional charge to the political authorities was sounding less and less plausible in the increasingly pluralistic societies of Europe and North America.

22 August 2017

Abraham Kuyper and the Pluralist Claims of the Liberal Project, Part 3: What Liberalism Implies for the Two Pluralisms

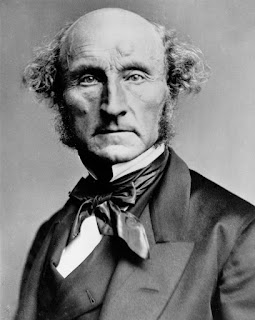

|

| John Stuart Mill |

There are two implications to this liberal move. First, it is incapable of accounting for structural differences among an assortment of communities. State and church are not essentially different from the garden club or the Boy Scouts. Whatever differences appear to the casual observer can be ascribed to the collective wills of the individuals who make them up. Proponents are persuaded that, even if different groups of citizens operate out of divergent comprehensive doctrines, they must be made to look beneath these commitments to what are believed to be the raw data of human experience that bind all persons together. These data are, of course, the constituent individuals themselves.

Every community can be easily understood as a collection of individuals who choose to be part of it for reasons peculiar to each member. There is nothing unusual about this approach, the liberal insists. Michael Ignatieff believes himself justified in asserting that liberal individualism is not peculiarly western or historically conditioned; it is human and universal: “It’s just a fact about us as a species: we frame purposes individually, in ways that other creatures do not.” Therefore if the claims of groups and individuals come into conflict, as they inevitably must, Ignatieff confidently concludes that “individual rights should prevail,” despite the contrary claims of nationalists, socialists and many conservatives of a communitarian bent.

15 August 2017

Abraham Kuyper and the Pluralist Claims of the Liberal Project, Part 2: The Church as Voluntary Association

|

| John Locke |

If, for example, we were to agree with John Locke’s definition of the church, we would find ourselves in territory foreign to the mainstream of the historic faith. According to Locke, “A church, then, I take to be a voluntary society of men, joining themselves together of their own accord in order to the public worshipping of God in such manner as they judge acceptable to Him, and effectual to the salvation of their souls” (emphasis mine). While there are undoubtedly many Christians, especially protestants in the free-church tradition, who would implicitly agree with Locke’s definition, the mainstream of the Christian tradition has viewed the church as the covenant community of those who belong to Jesus Christ, who is its Saviour and head.

Moreover, the gathered church, as distinct from the corpus Christi which is more encompassing, has been generally recognized to be an authoritative institution with the power to bind and loose on earth (Matthew 16:19, 18:18). As such it is more than the aggregate of its members but is a divinely-ordained vessel bearing the gospel to the world and especially to the church’s members.

09 August 2017

Abraham Kuyper and the Pluralist Claims of the Liberal Project, Part 1: Liberalism and Two Kinds of Diversity

Although it can be misleading to seek the meaning of commonly-used words and expressions in their etymological origins, in the case of liberalism, the linguistic connection with liberty is all too obvious. The promise of liberty is an attractive one that holds out the possibility of living our lives as we see fit, free from constraints imposed from without. We simply prefer to have our own way and not to have to defer to the wills of others.

Yet even the most extensive account of liberty must recognize that it needs to be subject to appropriate limits if we are not to descend into a chaotic state of continual conflict, which English philosopher Thomas Hobbes memorably labelled a bellum omnium contra omnes, a war of all against all.

Here I propose to compare two approaches to liberty, viz., those of liberalism and of the principled pluralism associated with the heirs of the great Dutch statesman and polymath, Abraham Kuyper. Although each claims to advance liberty, I will argue that the Kuyperian alternative is superior to the liberal because it is based on a more accurate appraisal of human nature, society and the place of community within it.

Yet even the most extensive account of liberty must recognize that it needs to be subject to appropriate limits if we are not to descend into a chaotic state of continual conflict, which English philosopher Thomas Hobbes memorably labelled a bellum omnium contra omnes, a war of all against all.

Here I propose to compare two approaches to liberty, viz., those of liberalism and of the principled pluralism associated with the heirs of the great Dutch statesman and polymath, Abraham Kuyper. Although each claims to advance liberty, I will argue that the Kuyperian alternative is superior to the liberal because it is based on a more accurate appraisal of human nature, society and the place of community within it.

28 July 2017

Happy AR Day! a holiday to counter Bastille Day

|

| G. Groen van Prinsterer |

There are now 351 days remaining until the next Bastille Day. As we await its occurrence, I would like to propose for that day a counter-holiday to be titled AR Day, “AR” standing for Anti-Revolutionary. After the generation of war and instability set off in 1789 finally ended with Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, many Europeans, especially those still loyal to the gospel of Jesus Christ, set about attempting to combat the ideological illusions the Revolution had engendered. This entailed breaking with the modern preoccupation—nay, obsession—with sovereignty and recovering a recognition of the legitimate pluriformity of society.

In any ordinary social setting, people owe allegiance to a variety of overlapping communities with differing internal structures, standards, and purposes. These are sometimes called mediating structures, intermediary communities or, taken collectively, civil society. This reality stands in marked contrast to liberal individualism and such collectivist ideologies as nationalism and socialism, each of which is monistic in its own way—locating a principle of unity in a human agent to which it ascribes sovereignty, or the final say.

Recognizing that the only source of unity in the cosmos is the God who has created and redeemed us in the person of his Son, Christians are freed from the need to locate a unifying source within the cosmos. Thus the institutional church can be itself, living up to its divinely-appointed mandate to preach the gospel, administer the sacraments, and maintain discipline. The family is free to be the family, nurturing children as they grow to maturity. Marriage is liberated to be itself, free from the stifling constraints of the thin contractarian version now extolled in North America and elsewhere. And, of course, the huge array of schools, labour unions, business enterprises, and voluntary associations have their own proper places, not to be artificially subordinated to an all-embracing state or the imperial self.

This pluriformity is something worth celebrating! It may sound perfectly mundane when described in the way I have here, but the fact that the followers of today’s political illusions find it so threatening indicates that we cannot afford to take it for granted. Here are some suggested readings that highlight this dissenting anti-revolutionary tradition:

- Johannes Althusius, Politics (1614)

- Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790)

- Guillaume Groen van Prinster, Unbelief and Revolution (1847)

- Abraham Kuyper, Our Program (1880)

- Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum (1891)

- Jacques Maritain, Man and the State (1951)

- Yves R. Simon, Philosophy of Democratic Government (1951)

- Friedrich Julius Stahl, Philosophy of Law: the Doctrine of State and the Principles of State Law (1830)

Music will consist of mass communal singing of the Psalms, preferably from the Genevan Psalter. Additional music will be provided by (why not?) the monks of the Abbaye Saint-Pierre in Solesme! Let’s do it!

This is a numerically altered version of David Koyzis's debut column at Kuyperian Commentary.

10 July 2017

To my students: a reluctant farewell

When I began teaching thirty years ago, I had not anticipated how much I would grow to love the young people in my classes. At Notre Dame during my graduate student years, I had been just another teaching assistant, and thus one more obstacle for the ambitious undergraduates to get past on their way to (for most of them, it seemed) law school. All of that changed when I arrived at what was still called Redeemer College in the autumn of 1987.

In the first course I taught, an introductory political science course, I made a number of missteps—nothing serious, just the ordinary kind that come with inexperience. Nevertheless, at the end of the term, when I read the student evaluations, quite a number of them generously offered this assessment: “Has potential to become an excellent professor.” This could have become a deflating experience, but instead I took heart from their words, and it became an incentive for me to improve my performance in the classroom.

The early years were, of course, filled with the normal stresses of multiple preparations of courses from the ground up. Many a beginning teacher reports that her ambition is simply to keep up with the students from day to day, and that was my experience as well. Nevertheless, despite all the busyness, I made time outside the classroom to be with my students and to converse with them. In the process I found that I was developing a deep love for them which lasted for three decades.

Two episodes stand out for me.

Not long into my teaching career, I was sitting at a cafeteria table with several of my students. One young lady repeated to me something I had said in class as though it were gospel truth, and I was startled and somewhat alarmed at the influence I was already having on her. That night I was unable to sleep, as the words of James 3 echoed through my head: “Let not many of you become teachers, my brethren, for you know that we who teach shall be judged with greater strictness.” I quickly recovered, of course, but I was beginning to comprehend the awesome responsibility that teachers carry for communicating truth to the young people in their care.

The second episode occurred after I was married and shortly after our daughter was born three months premature. Theresa had been in two successive hospitals for more than ten weeks after her early birth. Still less than five pounds when she went home with us, she was released from hospital on the very day that Ontario’s Golden Horseshoe was hit by a snowstorm of historic proportions. (Remember when Toronto’s mayor called on federal troops to help dig his city out?) Not knowing what to do, I phoned one of my students on campus, and he brought some of his friends over to our house. They freed our driveway in little time, and we were able to get to St. Joseph’s Hospital on schedule to bring Theresa home. This young man, now in his forties, is still a close friend.

To all of you whom I was privileged to teach over the decades, know that you have my undying affection and loyalty. I have sought above all to show you that the belief that our world belongs, not to ourselves, but to the God who has created and redeemed us has huge implications for political life and for the animating visions underpinning it. I hope I have communicated to you a hunger for justice, especially for the most vulnerable in our society as well as for the communities that support them. My greatest prayer for you is that you will continue to be agents of God’s kingdom in this world for whom Christ died.

In the meantime, although I am unwillingly leaving my current students behind, I fully intend to maintain the friendships I have formed over the years with so many of you. Do stay in touch!

After thirty years of service at Redeemer University College, David Koyzis’ position was terminated due to financial and curricular restructuring. He is currently seeking employment elsewhere and asks for readers’ prayers in the meantime.

In the first course I taught, an introductory political science course, I made a number of missteps—nothing serious, just the ordinary kind that come with inexperience. Nevertheless, at the end of the term, when I read the student evaluations, quite a number of them generously offered this assessment: “Has potential to become an excellent professor.” This could have become a deflating experience, but instead I took heart from their words, and it became an incentive for me to improve my performance in the classroom.

The early years were, of course, filled with the normal stresses of multiple preparations of courses from the ground up. Many a beginning teacher reports that her ambition is simply to keep up with the students from day to day, and that was my experience as well. Nevertheless, despite all the busyness, I made time outside the classroom to be with my students and to converse with them. In the process I found that I was developing a deep love for them which lasted for three decades.

Two episodes stand out for me.

Not long into my teaching career, I was sitting at a cafeteria table with several of my students. One young lady repeated to me something I had said in class as though it were gospel truth, and I was startled and somewhat alarmed at the influence I was already having on her. That night I was unable to sleep, as the words of James 3 echoed through my head: “Let not many of you become teachers, my brethren, for you know that we who teach shall be judged with greater strictness.” I quickly recovered, of course, but I was beginning to comprehend the awesome responsibility that teachers carry for communicating truth to the young people in their care.

The second episode occurred after I was married and shortly after our daughter was born three months premature. Theresa had been in two successive hospitals for more than ten weeks after her early birth. Still less than five pounds when she went home with us, she was released from hospital on the very day that Ontario’s Golden Horseshoe was hit by a snowstorm of historic proportions. (Remember when Toronto’s mayor called on federal troops to help dig his city out?) Not knowing what to do, I phoned one of my students on campus, and he brought some of his friends over to our house. They freed our driveway in little time, and we were able to get to St. Joseph’s Hospital on schedule to bring Theresa home. This young man, now in his forties, is still a close friend.

To all of you whom I was privileged to teach over the decades, know that you have my undying affection and loyalty. I have sought above all to show you that the belief that our world belongs, not to ourselves, but to the God who has created and redeemed us has huge implications for political life and for the animating visions underpinning it. I hope I have communicated to you a hunger for justice, especially for the most vulnerable in our society as well as for the communities that support them. My greatest prayer for you is that you will continue to be agents of God’s kingdom in this world for whom Christ died.

In the meantime, although I am unwillingly leaving my current students behind, I fully intend to maintain the friendships I have formed over the years with so many of you. Do stay in touch!

After thirty years of service at Redeemer University College, David Koyzis’ position was terminated due to financial and curricular restructuring. He is currently seeking employment elsewhere and asks for readers’ prayers in the meantime.

26 June 2017

Religion's apparent threat to sovereignty: Rousseau, Sanders and the religious test for public office

During last year's presidential election campaign, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, a latecomer to the Democratic Party, positioned himself as a voice for the downtrodden against big moneyed interests, something that many Americans, especially the young, found deeply attractive. In so doing, Sanders drew on a deep tradition of social justice with biblical roots, as evidenced in his powerful address to Liberty University two years ago. Recognizing that “there is no justice when so few have so much and so many have so little,” he laudably demonstrated his concern for the economically disadvantaged in our society. However, judging from his questioning last week of Russell Vought, the President's nominee for deputy director of the Office of Management and Budget, Sanders appears not to understand that there is no justice where religious liberty lacks protection.

At issue was a blog post Vought had written as an alumnus of Wheaton College, a Christian university near Chicago, in response to a controversy involving one of its faculty members. The offending passage was this: “Muslims do not simply have a deficient theology. They do not know God because they have rejected Jesus Christ his Son, and they stand condemned.” While it may sound harsh to a nonchristian, Vought was in no way suggesting that Muslims cannot be good citizens or should be treated severely by the governing authorities. He was simply reiterating what the vast majority of Christians have believed for two millennia: that Jesus is the way, the truth and the life, and that no one comes to the Father except through him (John 14:7).

At issue was a blog post Vought had written as an alumnus of Wheaton College, a Christian university near Chicago, in response to a controversy involving one of its faculty members. The offending passage was this: “Muslims do not simply have a deficient theology. They do not know God because they have rejected Jesus Christ his Son, and they stand condemned.” While it may sound harsh to a nonchristian, Vought was in no way suggesting that Muslims cannot be good citizens or should be treated severely by the governing authorities. He was simply reiterating what the vast majority of Christians have believed for two millennia: that Jesus is the way, the truth and the life, and that no one comes to the Father except through him (John 14:7).

20 June 2017

Grace and justice: a response to Brunton

The Gospel Coalition's website tells us that, "as a broadly Reformed network of churches, [it] encourages and educates current and next-generation Christian leaders by advocating gospel-centered principles and practices that glorify the Savior and do good to those for whom he shed his life's blood." Founded by Donald A. Carson and Manhattan pastor Tim Keller in 2005, it publishes numerous articles reflecting its commitment to renewing churches through proclaiming the gospel. I have published with them once, and an interview with me recently appeared on their website.

Last year Jacob Brunton posted a critique of TGC which recently came to my attention: How The Gospel Coalition is Killing The Gospel With “Social Justice”. Brunton laments what he sees as the substitution in many circles of "economic justice" for "charity."

Well, not exactly. To begin with, Brunton's argument is missing a recognition of what Abraham Kuyper calls sphere sovereignty, one of whose implications is that justice's meaning must be qualified by context. In marriage justice requires that husband and wife be faithful to each other. In the state justice demands that government treat equitably individuals and the variety of communities of which they are part. In the classroom justice calls both instructor and students to fulfil their responsibilities relative to the educational mission that governs their relationship. So, yes, justice may mean something different in the institutional church context than in the state, the business enterprise, the school, the labour union, &c.

More seriously, Brunton risks confusing God's relationship with us on the one hand and our multifaceted relationships with each other on the other hand. God relates to us as Creator to creature, while we relate to each other as fellow creatures under God. One needs to be cautious in drawing too close an analogy between God's unmerited grace, which we do not deserve, and the creational contexts rightly ordered by the jural norms conditioning ordinary human interchange. If someone buys my house, then, once I've turned over the keys to him, he definitely owes me the amount of money we had agreed on irrespective of whether either of us has received God's saving grace.

The crucial difference here is that God is God and we are not. As his creatures, we confess that our very existence is conditional on his freely granting us life. God owes us nothing. But this is definitely not true of our relations to each other, whether in the context of ordinary economic life or in the realm of assisting the poor to fulfil their respective callings. Whether such help for the poor is deserved or unmerited must be weighed according to a variety of factors related to the norms for economic life and not by analogy to God's relationship to his people. For example, is poverty a byproduct of lack of effort? Or is economic life structured in such a way as to exclude indefinitely certain segments from its benefits? Either or both may be true. Who deserves what will depend on how we assess a variety of economic and other factors based on observation, synthesis and analysis of conditions on the ground.

What we ought not to do is pretend that a correct theology of grace will by itself give us an answer to the complexities of economic life in our society.

Last year Jacob Brunton posted a critique of TGC which recently came to my attention: How The Gospel Coalition is Killing The Gospel With “Social Justice”. Brunton laments what he sees as the substitution in many circles of "economic justice" for "charity."

Remember that I said charity is a picture of the gospel? That’s why it’s such an important practice for the Church: it demonstrates the grace of God. Now, ask yourself this: if charity is a picture of the grace of God in the gospel, then what message are we sending about the grace of God, and about the gospel, when we preach that charity is deserved? Answer: We are teaching that God’s grace is, likewise, deserved. When we teach that we owe money to the poor, we are teaching that God owed us the cross. When we teach that the poor deserve monetary assistance, we are teaching that we deserved what Christ accomplished for us. When we teach that “economic justice” consists of giving to those in need, we are teaching that divine justice consists of the same — and the inevitable result is a grace-less universalism in which everyone gets all the blessings of heaven, because they need it. You cannot pervert the meaning of justice in “society” or in the “economy,” and not expect it to bleed over into theology. You cannot have one standard of justice in Church on Sunday morning, and another for the world the rest of the week.

Well, not exactly. To begin with, Brunton's argument is missing a recognition of what Abraham Kuyper calls sphere sovereignty, one of whose implications is that justice's meaning must be qualified by context. In marriage justice requires that husband and wife be faithful to each other. In the state justice demands that government treat equitably individuals and the variety of communities of which they are part. In the classroom justice calls both instructor and students to fulfil their responsibilities relative to the educational mission that governs their relationship. So, yes, justice may mean something different in the institutional church context than in the state, the business enterprise, the school, the labour union, &c.

More seriously, Brunton risks confusing God's relationship with us on the one hand and our multifaceted relationships with each other on the other hand. God relates to us as Creator to creature, while we relate to each other as fellow creatures under God. One needs to be cautious in drawing too close an analogy between God's unmerited grace, which we do not deserve, and the creational contexts rightly ordered by the jural norms conditioning ordinary human interchange. If someone buys my house, then, once I've turned over the keys to him, he definitely owes me the amount of money we had agreed on irrespective of whether either of us has received God's saving grace.

The crucial difference here is that God is God and we are not. As his creatures, we confess that our very existence is conditional on his freely granting us life. God owes us nothing. But this is definitely not true of our relations to each other, whether in the context of ordinary economic life or in the realm of assisting the poor to fulfil their respective callings. Whether such help for the poor is deserved or unmerited must be weighed according to a variety of factors related to the norms for economic life and not by analogy to God's relationship to his people. For example, is poverty a byproduct of lack of effort? Or is economic life structured in such a way as to exclude indefinitely certain segments from its benefits? Either or both may be true. Who deserves what will depend on how we assess a variety of economic and other factors based on observation, synthesis and analysis of conditions on the ground.

What we ought not to do is pretend that a correct theology of grace will by itself give us an answer to the complexities of economic life in our society.

11 May 2017

Youth and age, energy and wisdom

|

| The Arrogance of Rehoboam, Hans Holbein the Younger |

The Bible has much to say about the wisdom that comes with age: “You shall rise up before the hoary head, and honour the face of an old man, and you shall fear your God: I am the Lord” (Lev. 19:32). “Wisdom is with the aged, and understanding in length of days” (Job 12:12). “The righteous flourish like the palm tree, and grow like a cedar in Lebanon. . . . They still bring forth fruit in old age” (Ps. 92:12,14). These are not just isolated proof texts. The wisdom of old age is a theme found throughout Scripture.

Moses, we learn in Exodus, was 80 years old and his brother Aaron 83 when they were called to liberate the Israelites from their slavery in Egypt (Ex. 7:7). In Canadian terms, Moses would have been eligible for his CPP pension 15 years earlier, after having laboured for more than half a century. Yet God still had work ahead for him – vastly more important than anything he had accomplished as an adopted prince of Egypt. Jews, Christians and Muslims alike regard Moses as a hero of their respective faiths, recognizing that God’s call can come even when we assume that our fruitfulness is declining or at an end.

In 1 Kings 12 we are told that, after King Solomon’s death, his son Rehoboam was faced with rebellion by the northern tribes and was confronted with a stark choice: to continue the misguided policy of his father in conscripting only non-Judahites into forced labour, or to treat them more equitably. The elders in the kingdom advised him to acquiesce in the legitimate demands of the northerners: “If you will be a servant to this people today and serve them, and speak good words to them when you answer them, then they will be your servants for ever” (vs. 7).

But Rehoboam also consulted the young men with whom he had grown up, and they gave him different advice: “Thus shall you say to them, ‘My little finger is thicker than myfather’s loins. And now, whereas my father laid upon you a heavy yoke, I will add to your yoke. My father chastised you with whips, but I will chastise you with scorpions’” (vs 10-11). Rehoboam was undoubtedly impressed with the intellectual brilliance and youthful vigour of this second group of advisors in contrast to the less appealing demeanour of the first. Yet following youthful advice resulted in his losing most of the old kingdom of Israel, with only Judah and part of Benjamin remaining under his sovereignty.

Today many organizations – from churches and businesses to schools and governments – are tempted to run with the young. After all, they are less expensive, their formal education is more recent, and they are brimming with new ideas with potential benefits for all stakeholders. And, face it, the young present a fresher appearance to the outside world, ready to tackle the challenges ahead and to put aside the past. Christian organizations are not immune to the pressure to rejuvenate their images and to sideline those with more experience.

While many jurisdictions have enacted legislation prohibiting age discrimination, it is not too difficult for organizations to find ways around this. But this should not be the main issue. The fact is that no community, whatever its purpose, can afford to reinvent the wheel and to keep repeating the mistakes of the past. It is for this reason that the Bible associates wisdom with age and experience. We should too.

05 May 2017

Announcement: emeritus status

As many of you know, not quite two months ago, I was laid off from my thirty-year position at Redeemer University College due to financial constraints and programme restructuring. At the time I was told that I would not be eligible for emeritus status.

This week I was informed that the Senate and Board of Governors have approved emeritus status for me after all.

Nevertheless, I am still seeking opportunities for service in other contexts after the next academic year. I am grateful for the large numbers of people who have expressed support for me in recent weeks, and I would appreciate your continued prayers.

Thanks so much.

David Koyzis

This week I was informed that the Senate and Board of Governors have approved emeritus status for me after all.

Nevertheless, I am still seeking opportunities for service in other contexts after the next academic year. I am grateful for the large numbers of people who have expressed support for me in recent weeks, and I would appreciate your continued prayers.

Thanks so much.

David Koyzis

14 April 2017

How 18th-century Virginians nearly made the United States more like Canada

|

| James Madison |

The reality is a little more complicated, as F. H. Buckley reports in his book, The Once and Future King: The Rise of Crown Government in America (Encounter Books, 2014). James Madison is often said to be one of the key architects of the Constitution of the United States, primarily because he defended it so eloquently in the Federalist Papers, a series of essays written to persuade the states to sign on to the new union. While this effort was successful, few are aware that Madison actually got little of what he had originally wanted out of the meetings held during the summer of 1787.

The majority of delegates to the constitutional convention thought the popular election of a president a very bad idea indeed. Better, they thought, to tether the chief executive to Congress, which would be responsible for putting him in office. Madison was one of a group of delegates from Virginia, arguably the most significant of the thirteen states and certainly the principal catalyst for bringing them together.

The Virginia Plan would have created a two-chamber legislature, the first chamber being directly elected by voters. The first chamber would in turn appoint the members of the second, and the two together would appoint a president, who would remain dependent on them for his power. In short, the Virginia Plan would have made the United States into a parliamentary system similar to Canada and Great Britain. Needless to say, the Virginians, including Madison, did not get their way, and we now associate Madison with a separation of powers constructed not so much out of principle as out of compromise between the larger and smaller states.

However, one element was missing from the ill-starred Virginia Plan. If, like our prime minister, the chief executive was to be dependent on Congress, the Virginians neglected to consider the need for a distinct head of state who would be counterpart to the monarch. We may think of the Queen and her representatives as ornamental fixtures in our own constitutional system, but this is not so. The principal role of the monarch is to ensure that there is always a government in place. She herself does not rule, but she must see to it that she has ministers in office capable of doing so. More significant yet, the Queen plays an essential unifying role that no mere prime minister can do. As J. R. Mallory put it, the monarchy

denies to political leaders the full splendour of their power and the excessive aggrandizement of their persons which come from the undisturbed occupancy of the centre of the stage. The symbolic value of the face of the leader on the postage stamp, the open and undisguised role of the leader and redeemer of the people, are hints of the threatened presence of the one-party state.

Indeed, as Buckley points out, the majority of countries with American-style presidential systems have gone through periods of dictatorship, and the concentration of executive power in one person makes this more likely.

By contrast, parliamentary systems with a divided executive tend disproportionately to be stable and more democratic for longer periods of time. This includes constitutional monarchies, like Britain and the Netherlands, but also parliamentary republics such as Germany, where a president serves as head of state and a chancellor as head of government.

If Madison and his fellow Virginians had had their way back in 1787, today the United States might look more like, well, us!

Principalities & Powers, Christian Courier, April 2017.

13 April 2017

Interview with Ashford

Bruce Ashford, Professor and Provost at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, has posted an interview with me. Here is an excerpt on the subject of contemporary libertarianism:

Libertarianism is really an early form of liberalism that was recovered in the 20th century by the likes of Friedrich Hayek, Ludwig von Mises and others. It follows a principle articulated by John Stuart Mill in the 19th century, sometimes known as the harm principle. It runs like this: “the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.” Originally this was intended to apply only to the state, whose coercive power must be kept within strict bounds. From the libertarian perspective, a parliamentary body should not be legislating morality. The state makes no effort to impose and enforce social mores on the larger polity, and individuals should be granted the widest possible space for exercising their liberty. As long, of course, as they do not injure others.

However, at this latest stage in the liberal project, there has been a concerted effort to extend Mill’s harm principle into other areas of life where it does not really belong. In the real world all communities impose standards on their members, and not all of these are related to protecting them from injury or from doing harm. For example, a church congregation expects its members to confess the Christian faith and to live according to the Word of God. It further expects them to come together to worship God every week, even though their staying away for long stretches does no obvious harm to fellow members. Similarly, our daughter’s high school mandates the wearing of school uniforms. Not wearing the uniform does no evident injury to anyone, yet the school requires it all the same.

Our societies are made up of countless communities which impose on their members standards that vary from one to the next. Once the libertarian impulse has overtaken the state institution, it is difficult to limit it to the state alone. Yet if all communities were to adopt the harm principle and abandon the very standards that support their unique identity, the result would be an homogenizing of these communities. Every community, even marriage, family, church and state, becomes a mere voluntary association stripped of every claim to authoritative status. In this respect, libertarianism, which begins with a healthy suspicion of state action, ends in a kind of totalitarianism suspicious of all authorities and standards not rooted in the freely choosing wills of individuals.

30 March 2017

The Evolving American Constitution: Change Without Amendment

Might the United States be headed for significant constitutional change without formal amendment of the document we know as the Constitution?

One of the key features of the modern constitutional document is the amendment process, which is found in Article V of the US Constitution and in Part V of Canada's Constitution Act, 1982. Yet even without formal amendment, constitutions continue to develop, often simply through change in usage. In the Westminster tradition, the unwritten principles which govern a political system are known as conventions of the constitution, enduring for long periods of time and perhaps falling into desuetude when no longer deemed appropriate. In this way, the strong Tudor and inept Stuart monarchies gradually developed into constitutional monarchy, then parliamentary government, Cabinet government and, eventually, something approaching prime ministerial government. These are not insignificant changes in the ancient English constitution, yet the fundamental institutions have remained the same over many centuries, prompting Samuel Finer to call Great Britain's constitution “a democratic one, but poured into a medieval mold.”

Ironically, it was the American victory in the war for independence that led to the effective transfer of executive power from the king to the prime minister. But it was an even earlier event—a scandal, actually—that had led to the establishment of the office of prime minister itself half a century before.

King George I was the first of the Hanoverian monarchs called upon to rule, not only his German territories, but the two Kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, beginning in 1714 on the death of Queen Anne, the last of the Stuarts. Three factors prevented King George being a hands-on king. First, he was absent from Great Britain for about a fifth of his reign, preoccupied with matters in his Electorate of Hanover. Second, his mother tongue was German, and he spoke very little English, rarely meeting with his ministers, thus setting a binding precedent to be followed by later monarchs and their representatives. Third, his reign was plagued by scandal, politically incapacitating him and further empowering his advisers. In a 300-year-old precursor to the crashes of 1929 and 2008, the South Sea Bubble of 1720 impoverished many investors, implicating the King in this imaginative scheme connected to the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Thus discredited, George had to rely increasingly on his ministers, including one Robert Walpole, who became thereby the first prime minister, a post that came into existence almost by accident.

What we now know as the Westminster constitution, famously described by Walter Bagehot in The English Constitution (1867), was never planned. There were no founding fathers, no constitutional engineers weighing alternative political arrangements appropriate to the times. There was no Virginia Plan, New Jersey Plan or Connecticut Compromise. Political leaders simply adjusted their actions to changing circumstances within longstanding institutions. Canadian John Farthing aptly described the Westminster tradition in these words:

We all know, of course, that the Constitution of the United States was the product of hard-fought negotiations in Philadelphia during the summer of 1787. Or was it? Yes, the basic institutions were established then, but their subsequent functioning has been just as subject to the vagaries of history as the British and Canadian constitutions. This suggests that there is a larger unwritten American constitution whose principles are not easily captured in a single document but are based on a general respect for the rule of law. Until 1940, the two-term presidency was one such unwritten convention, established as a precedent by George Washington in 1797 and later codified in the Twenty-Second Amendment (1951).

Judicial review is another convention. Unmentioned in the text of the Constitution, the justices of the Supreme Court simply asserted it in Marbury v. Madison (1803), and no one bothered to stop them. The congressional power to declare war, enshrined in Article I, section 8, may be said to have become by convention a dead letter simply because it has not been invoked for three quarters of a century. And finally, the constantly changing relationships between federal and state governments on the one hand and between President and Congress on the other have developed in ways parallel to the shifting relationship between King and Parliament across the pond. Yet no formal amendment has wrought these profound changes. In other words, there is a case to be made that British and American constitutions are not that different after all.

F. H. Buckley has recently argued that the American founders originally desired, not so much a separation of powers, as congressional government, with a president dependent for his position on Congress, and not on the electorate. A century after the American founding, Woodrow Wilson, the only academic political scientist to become president, believed that the US was moving along the path pioneered by Westminster and expressed this view in his Congressional Government (1885). With a series of weak presidents following the Civil War, effective political power had passed to congressional leadership, with the Speaker of the House of Representatives, if not exactly becoming a de facto prime minister, nevertheless taking on an increasingly central role.

Present circumstances could see many of the founders and Wilson finally getting their way. As the current occupant of the White House is widely regarded as less than fully competent, and with many observers seriously questioning his ability to govern, effective political power could shift back to Congress, with congressional leaders increasingly taking the reins of government. This would require no formal amendment to the Constitution, yet the constitution in the broader unwritten sense is flexible enough to accommodate such a possibility.

Would this be a good or bad thing? Having lived in Canada for over three decades, I understand and appreciate the advantages of separating the offices of head of state and head of government, of forcing a government to defend its policies before the people's representatives on a daily basis, and of ensuring the easy removal of a government that has lost the ability to govern. Of course, not every form of government works everywhere. A constitution that serves Britain and Canada well may not be a good fit for Americans, who are famously attached to their political institutions and are convinced of their innate superiority. Nevertheless, it might be a very good thing to see the presidency cut down to size and to have the gap filled by the people's representatives in Congress. It has happened before, and it could happen again.

David Koyzis is the author of Political Visions and Illusions and We Answer to Another: Authority, Office and the Image of God. He has recently begun work on a new book exploring the relationship between political culture and governing institutions. A slightly different version of this was published at First Thoughts.

One of the key features of the modern constitutional document is the amendment process, which is found in Article V of the US Constitution and in Part V of Canada's Constitution Act, 1982. Yet even without formal amendment, constitutions continue to develop, often simply through change in usage. In the Westminster tradition, the unwritten principles which govern a political system are known as conventions of the constitution, enduring for long periods of time and perhaps falling into desuetude when no longer deemed appropriate. In this way, the strong Tudor and inept Stuart monarchies gradually developed into constitutional monarchy, then parliamentary government, Cabinet government and, eventually, something approaching prime ministerial government. These are not insignificant changes in the ancient English constitution, yet the fundamental institutions have remained the same over many centuries, prompting Samuel Finer to call Great Britain's constitution “a democratic one, but poured into a medieval mold.”

Ironically, it was the American victory in the war for independence that led to the effective transfer of executive power from the king to the prime minister. But it was an even earlier event—a scandal, actually—that had led to the establishment of the office of prime minister itself half a century before.

|

| Sir Robert Walpole, the first Prime Minister |

What we now know as the Westminster constitution, famously described by Walter Bagehot in The English Constitution (1867), was never planned. There were no founding fathers, no constitutional engineers weighing alternative political arrangements appropriate to the times. There was no Virginia Plan, New Jersey Plan or Connecticut Compromise. Political leaders simply adjusted their actions to changing circumstances within longstanding institutions. Canadian John Farthing aptly described the Westminster tradition in these words:

Our constitutional inheritance was the living product of a long process of historical growth and development, and the tradition it embodied is of an order already proven of value in dealing with changing conditions of life and with changing climates of opinion.For Farthing, Americans tied their Constitution “to the ideas and mental climate of the eighteenth century,” while the unwritten British constitution, because it is constantly evolving, “is in no way bound to or fettered by any historical epoch.” Farthing was the son of an Anglican bishop, and it was easy for Christians to defend the British constitution as the happy result of the workings of divine Providence.

We all know, of course, that the Constitution of the United States was the product of hard-fought negotiations in Philadelphia during the summer of 1787. Or was it? Yes, the basic institutions were established then, but their subsequent functioning has been just as subject to the vagaries of history as the British and Canadian constitutions. This suggests that there is a larger unwritten American constitution whose principles are not easily captured in a single document but are based on a general respect for the rule of law. Until 1940, the two-term presidency was one such unwritten convention, established as a precedent by George Washington in 1797 and later codified in the Twenty-Second Amendment (1951).

Judicial review is another convention. Unmentioned in the text of the Constitution, the justices of the Supreme Court simply asserted it in Marbury v. Madison (1803), and no one bothered to stop them. The congressional power to declare war, enshrined in Article I, section 8, may be said to have become by convention a dead letter simply because it has not been invoked for three quarters of a century. And finally, the constantly changing relationships between federal and state governments on the one hand and between President and Congress on the other have developed in ways parallel to the shifting relationship between King and Parliament across the pond. Yet no formal amendment has wrought these profound changes. In other words, there is a case to be made that British and American constitutions are not that different after all.

|

| A young Woodrow Wilson |

Present circumstances could see many of the founders and Wilson finally getting their way. As the current occupant of the White House is widely regarded as less than fully competent, and with many observers seriously questioning his ability to govern, effective political power could shift back to Congress, with congressional leaders increasingly taking the reins of government. This would require no formal amendment to the Constitution, yet the constitution in the broader unwritten sense is flexible enough to accommodate such a possibility.

Would this be a good or bad thing? Having lived in Canada for over three decades, I understand and appreciate the advantages of separating the offices of head of state and head of government, of forcing a government to defend its policies before the people's representatives on a daily basis, and of ensuring the easy removal of a government that has lost the ability to govern. Of course, not every form of government works everywhere. A constitution that serves Britain and Canada well may not be a good fit for Americans, who are famously attached to their political institutions and are convinced of their innate superiority. Nevertheless, it might be a very good thing to see the presidency cut down to size and to have the gap filled by the people's representatives in Congress. It has happened before, and it could happen again.

David Koyzis is the author of Political Visions and Illusions and We Answer to Another: Authority, Office and the Image of God. He has recently begun work on a new book exploring the relationship between political culture and governing institutions. A slightly different version of this was published at First Thoughts.

20 March 2017

Announcement: termination of employment

Friends:

This is to let you know that, after teaching political science at Redeemer University College for thirty years, I have been let go due to programme restructuring and budgetary constraints. Some of you may recall that I was nearly let go two years ago but was reprieved by the institution's senate. This time, however, my termination was approved by the senate and the board of governors. Accordingly I will not be teaching during the 2017-2018 academic year.

As I am approaching the normal retirement age, I may take that option at the end of that year, but, if so, under the conditions of my termination I will do so without receiving emeritus status from Redeemer. Instead I will use the next year for my own research and writing, as well as to seek other employment opportunities. If you know of any such opportunities, I would be grateful if you would let me know.

In the meantime, if you have young people who are considering university, please do consider Redeemer, where they will continue to receive a high-quality education.

I would appreciate your prayers for my family and me, as well as for my soon-to-be former employer.

Thank you.

David Koyzis

This is to let you know that, after teaching political science at Redeemer University College for thirty years, I have been let go due to programme restructuring and budgetary constraints. Some of you may recall that I was nearly let go two years ago but was reprieved by the institution's senate. This time, however, my termination was approved by the senate and the board of governors. Accordingly I will not be teaching during the 2017-2018 academic year.

As I am approaching the normal retirement age, I may take that option at the end of that year, but, if so, under the conditions of my termination I will do so without receiving emeritus status from Redeemer. Instead I will use the next year for my own research and writing, as well as to seek other employment opportunities. If you know of any such opportunities, I would be grateful if you would let me know.

In the meantime, if you have young people who are considering university, please do consider Redeemer, where they will continue to receive a high-quality education.

I would appreciate your prayers for my family and me, as well as for my soon-to-be former employer.

Thank you.

David Koyzis

09 January 2017

'No core identity'? The impossibility of the state without a soul

I am no friend of nationalism. Given what my paternal relatives experienced as refugees in their own country of Cyprus, I thoroughly detest the clashing ethnic nationalisms that tore apart the island. I hate what the Turks did to the Armenians in 1915 and what they did to the Greeks of Smyrna seven years later. I dislike what Serbs did to Croats and vice versa. And, of course, I need hardly mention the Holocaust ruthlessly implemented for the sake of an ethnically pure Germany.

That said, I cannot endorse Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's assertion that Canada is "the first postnational state," as indicated in this article from The Guardian: The Canada experiment: is this the world's first 'postnational' country? Here is author Charles Foran:

Trudeau's description calls up some very strange mental images. One might envision a robot programmed to do all, or most, of the things a human being can do, but, like the unfortunate tin woodman in The Wizard of Oz, lacking a heart. In Canada we like to think that our identity resides in our very lack of identity. Not satisfied with citizenship in a soulless nation, some go so far as to assert that what defines Canada is its universal health care. But neither of these will work, and they certainly will not satisfy the human soul.

Following the late Benedict Anderson, we might call a nation an imagined community, given that we do not naturally feel a sense of kinship and camaraderie with those living even half an hour from us, much less on the other side of the country. But this is all the more reason for a country to cultivate and maintain certain intangibles that cannot simply be created de novo. Even the most diverse of nations requires some sort of commonality, that is, certain shared assumptions about life that set the tone for the larger society and for just governance. A common culture—especially political culture—is needed if a nation is to be more than just a collection of insular tribes under a political order so abstract as to be unable to command popular support.

Such shared assumptions need not be based on skin colour or blood ancestry. We needn't follow Gus Portokalos from My Big Fat Greek Wedding in asserting that there are two kinds of people in the world: Greeks and those who wish they were Greeks. There is no reason to conclude that our nation is the biggest and best in all respects and has a special mission to fulfil, based simply on the fact that we happen to live here. This is jingoism at its worst. Nevertheless, a nation should include at least such elements as common commitment to the rule of law, generally-accepted limits on political power and rhetoric, belief in constitutional governance, the rights of citizens, etc. English-speaking democracies have generally excelled at cultivating this political sense of nationhood better than many continental European countries whose governing institutions have not yet stood the test of centuries.

The danger of Justin Trudeau's rhetoric, however well meant, is that it may provide a pretext for government to manage all this diversity if it gets out of hand. Such government management will not, of course, be devoid of assumptions about the best way of life. The political managers will operate on the basis of their own worldviews, which in some sense they will be imposing on everyone else. As Fr. Richard John Neuhaus correctly observed more than three decades ago, a naked public square cannot long remain naked. Some comprehensive doctrine—some "thick" conception of human life—will inevitably fill the vacuum. If this is true in political life, it is also true in social life. Canadians, like Americans, cherish the contributions made by their immigrants, whom they have generally welcomed. But immigrants have come here, not because Canada has no core identity, but precisely because of Canada's core political identity: a stable democracy with a vibrant tradition of the rule of law rooted in British and French precedents. More to the point, this core identity is unlike the political cultures these immigrants have left behind.

Common assumptions, usages and customs, passed down through the generations, infuse life into a nation and generally preclude the necessity of government's micromanaging the larger society. A government that makes a policy of denying the normative character of these customs in favour of a vague multiculturalism does so at the peril of the larger culture to which it owes, yes, its own core identity as a constitutional government.

A slightly different version is posted at First Thoughts.

That said, I cannot endorse Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's assertion that Canada is "the first postnational state," as indicated in this article from The Guardian: The Canada experiment: is this the world's first 'postnational' country? Here is author Charles Foran:

But as well as practical considerations for remaining an immigrant country, Canadians, by and large, are also philosophically predisposed to an openness that others find bewildering, even reckless. The prime minister, Justin Trudeau, articulated this when he told the New York Times Magazine that Canada could be the “first postnational state”. He added: “There is no core identity, no mainstream in Canada.”

The remark, made in October 2015, failed to cause a ripple – but when I mentioned it to Michael Bach, Germany’s minister for European affairs, who was touring Canada to learn more about integration, he was astounded. No European politician could say such a thing, he said. The thought was too radical.

For a European, of course, the nation-state model remains sacrosanct, never mind how ill-suited it may be to an era of dissolving borders and widespread exodus. The modern state – loosely defined by a more or less coherent racial and religious group, ruled by internal laws and guarded by a national army – took shape in Europe. Telling an Italian or French citizen they lack a “core identity” may not be the best vote-winning strategy.

Trudeau's description calls up some very strange mental images. One might envision a robot programmed to do all, or most, of the things a human being can do, but, like the unfortunate tin woodman in The Wizard of Oz, lacking a heart. In Canada we like to think that our identity resides in our very lack of identity. Not satisfied with citizenship in a soulless nation, some go so far as to assert that what defines Canada is its universal health care. But neither of these will work, and they certainly will not satisfy the human soul.

Following the late Benedict Anderson, we might call a nation an imagined community, given that we do not naturally feel a sense of kinship and camaraderie with those living even half an hour from us, much less on the other side of the country. But this is all the more reason for a country to cultivate and maintain certain intangibles that cannot simply be created de novo. Even the most diverse of nations requires some sort of commonality, that is, certain shared assumptions about life that set the tone for the larger society and for just governance. A common culture—especially political culture—is needed if a nation is to be more than just a collection of insular tribes under a political order so abstract as to be unable to command popular support.

Such shared assumptions need not be based on skin colour or blood ancestry. We needn't follow Gus Portokalos from My Big Fat Greek Wedding in asserting that there are two kinds of people in the world: Greeks and those who wish they were Greeks. There is no reason to conclude that our nation is the biggest and best in all respects and has a special mission to fulfil, based simply on the fact that we happen to live here. This is jingoism at its worst. Nevertheless, a nation should include at least such elements as common commitment to the rule of law, generally-accepted limits on political power and rhetoric, belief in constitutional governance, the rights of citizens, etc. English-speaking democracies have generally excelled at cultivating this political sense of nationhood better than many continental European countries whose governing institutions have not yet stood the test of centuries.