I am part of what may have been the last generation of English-speaking Christians to grow up with the

King James Version of the Bible. This was the Bible we read in church and it shaped the liturgical patterns of our worship. We children memorized verses from it in sunday school, thereby giving it an intimate familiarity to us that has not been matched by any subsequent translation.

To be sure, the

Revised Standard Version had come out three years before I was born, but our church, a confessionally Reformed church, did not read from it, perhaps because of such controversial translations as that for Isaiah 7:14, which substituted "

young woman" for "

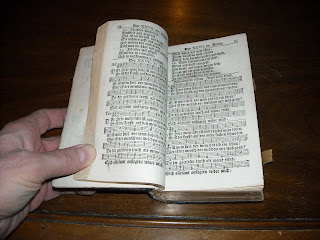

virgin." What we did not know, of course, is that, when the KJV was first published back in 1611, the

Geneva Bible was the translation preferred by our Reformed forebears, who were suspicious of the king's motives in commissioning a replacement. Nevertheless, over the long term the KJV won out over competing translations, retaining a cherished place in the hearts of English-speaking Christians for 350 years.

Protestant Christians, that is. In that world of half a century ago our use of the KJV underscored our differences with Roman Catholics, who read the 16th/17th-century

Douai-Rheims Bible, a translation from the Latin Vulgate. In the KJV we English-speaking protestants possessed a common Bible whose cadences we knew thoroughly and which constituted a shared heritage that in some sense we took for granted. This was

our Bible and always would be. We had a duty to read it and hear it in church. To be sure, given its archaic language, the KJV was not always easy to understand. Moreover, despite the claim of some contemporary KJV loyalists to love its superb literary qualities, it is no longer clear to us whether its language really

is poetic or whether it sounds poetic to us simply because it is from the KJV.

We all know the flaws in the KJV. It was translated from texts finalized in the 16th century, which have long since been superseded by superior Hebrew and Greek texts based on much earlier manuscripts. It contains numerous readings not attested to in the latter and of questionable authenticity — and presumably canonicity as well. I myself am far from urging a wholesale return to the KJV, although I believe it definitely worth celebrating during its 400th anniversary year.

The problem is that, while my generation of protestants grew up with a common Bible, no subsequent translation, however superior, has managed altogether to replace the KJV. By 1977 an expanded edition of the RSV had come to include the apocryphal/deuterocanonical books, thereby making it the closest we would come to a Common Bible for all Christians — protestants, Catholics and Orthodox. Yet ultimately it failed to catch on at the grassroots level. We now live with a ridiculously large number of Bible translations in English at the beginning of the second decade of this century. The multiplication of Bible versions shows no signs of slowing down, much less stopping.

For 30-some years the New International Version was the largest-selling Bible in the English-speaking world, considerably outpacing the RSV and KJV alike. But two months ago the International Bible Society released an

updated version of the NIV which may fail to catch on, if recent controversies are any indication. Although

I was initially sceptical that the

English Standard Version would supplant the NIV, I now think it has a fighting chance if the

NIV 1984 is no longer to be available, except online.

Will any of these translations still be read 400 years from now? It would be foolish to predict so far into the future, but it seems unlikely that any will equal the King James Version not only in terms of longevity, but in its capacity to shape the language and culture of the English-speaking peoples.