Quite coincidentally my wife gave me for my birthday two DVDs, Alfred Hitchcock's Rope and Aleksandr Sokurov's Russian Ark, unaware that both represent similar cinematic experiments more than half a century apart.

It was the Russian film director Sergei Eisenstein who pioneered the use of montage, a technique juxtaposing different camera shots of a single event and of related events to create an overall impression of the action. The use of this technique requires editing of sometimes very brief scenes into a thematic whole, something that has become so standard in film-making that we can hardly imagine it could be otherwise. (Apparently it also facilitated the work of Soviet-era censors!) Here is an example from Eisenstein's Aleksandr Nevsky:

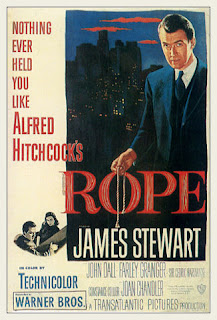

Yet what if a director were to shoot a film in one continuous take from beginning to end, without editing? Up until recently this was not possible, as conventional film reels contained only eight minutes of film. In 1948 Hitchcock attempted the next best thing in shooting Rope and thus sought to replicate something of the flavour of the theatre on the silver screen — or perhaps I should take back the "silver" part, because it was Hitch's first colour film.

A number of reviewers have labelled this technique a mere gimmick. Yet there are at least two things to be said in its favour. First, this is how we experience life in real time. Second, this is how actors act on the stage. There is more than an incidental relationship between the stage and the screen, with stage plays being constantly adapted for the screen and, rather less often, vice versa. Rope is certainly a good example of the former.

Nevertheless, it's a difficult thing to pull off, even when the technical issues have been surmounted, as in Sokurov's more recent offering. The actors have to be thoroughly rehearsed before they can begin to shoot. The script must be completed (many directors begin filming without a complete script). The actors must come in precisely on cue and cannot make a mistake. The director has to resist the temptation to call "Cut!" in the midst of a less than fully perfect scene. Compared to Sokurov, Hitch had it easy. After the eight minutes were up, the camera man would focus on the dark back of a suit coat and then pull back again, a rather too obvious attempt to cover up a change of reels. Yet even within these eight minutes, Hitch sometimes had to cut to another part of the room, due, one assumes, to an actor's mistake that had to be covered up. So, no, Rope is not a seamless whole.

Fast forward to the beginning of the 21st century. The technical obstacles have been conquered, and it is now possible to shoot a film in one continuous take. The old-fashioned reels are gone. A steadicam can be taken virtually anywhere, and the footage can go in digital format directly to a single disk. No need for editing. But now the whole enterprise becomes precarious indeed, especially if you have your "studio" for only one day. In Sokurov's case, his studio was the famed State Hermitage Museum, once the tsars' Winter Palace, in St. Petersburg, Russia. Museum officials gave him a single day to accomplish this unlikely feat. Had anything gone wrong, the effort would have had to be abandoned, with much time and expense wasted. Yet after three (or four, depending on whose account you read) attempts, Sokurov and his thousands of actors met with success, producing what in my opinion is a minor masterpiece.

Now to the films themselves, beginning with Rope, the story of two young men who murder a former classmate just for the thrill of it. The plot is borrowed from the Leopold and Loeb murder case of 1924. Here Brandon Shaw (John Dall) and Philip Morgan (Farley Granger) strangle David Kentley (Dick Hogan) in the opening scene. This is not a whodunit. The audience knows what has happened. The only real uncertainty is how long it will take their former teacher Rupert Cadell (Jimmy Stewart) to figure it out for himself and bring the killers to justice. After murdering their friend, the young men hide the body in a chest in the living room. They then proceed to host a party for the victim's family and fiancée, with a buffet dinner spread on top of the chest. This is supposed to be the perfect murder, committed by ostensibly superior human beings against a supposed inferior.

Made only three years after the end of the nazi régime in Germany, the film has a Nietzschean element running through it. Cadell has taught this worldview to his students and, egged on by Shaw, even makes a tongue-in-cheek speech extolling the benefits of murder to the guests at the party. Yet when Cadell discovers the truth and becomes aware of his own intellectual contribution to the crime, he rather suddenly becomes a liberal believer in equality and human rights, a transformation that not only comes a little too late but lacks plausibility — as if Heinrich Himmler could become John Rawls overnight.

Granger's character comes across as whiny. It is his scarcely concealed anxieties that arouse Stewart's suspicions and give away the truth. Granger would be an attractive and convincing actor in Hitchcock's Strangers on a Train three years later, but here he comes across as weak and snivelling — hardly the Nietzschean Übermensch required to pull off the perfect murder. I've not seen or read the play, so this flaw could perhaps be traceable to the original script by Patrick Hamilton.

Now on to Russian Ark. There is no plot as such in this film, which instead takes us on a tour of Russian history from Peter the Great through the horrific siege of Leningrad up to the present. In the opening scene the director wakes up from an apparent accident to find himself in St. Petersburg's Winter Palace surrounded by figures from the early 18th century, including Peter the Great himself, who founded the city. No one can see the director, except for the similarly misplaced Marquis de Custine, who alone is able to interact with the people they meet on this most unusual journey through Russian history.

In addition to meeting Catherine the Great, Nicholas I, Nicholas II and his family, and even Aleksandr Pushkin, we are treated to the magnificent art in the Hermitage's many rooms — most of which is European in origin. Here we see something of a subtext in Sokurov's work: Russia's ongoing, if sometimes fraught, relationship with Europe — or should I say the rest of Europe. The Winter Palace is like an ark bearing the best of European civilization through the turbulent waters of Russia's history. The final scene of the film (unless the film itself is understood to be one long scene) is of the last masquerade ball held in the Winter Palace in 1913, complete with orchestra and dancers, and even Pushkin — or perhaps someone dressed like him. Lovers of Russian history and culture will find this film a treat for the eyes and ears. Nevertheless, it will take some prior knowledge to make sense of Russian Ark. It is worth reading some of that country's history to be able fully to enjoy the experience. This is a film to savour over multiple viewings.

No comments:

Post a Comment