Nevertheless, a quarter century ago my impression of the university's administration, then headed by its long-serving president, Fr. Theodore Hesburgh, was that, while it tried its best to hold the line on its Catholic identity, it did so with some embarrassment, seeking respectability with the larger educational establishment and even with the popular media. Against the background of an establishment that traditionally viewed Roman Catholics as un-American, Notre Dame has coveted a place for itself as a genuinely American university. Of course, sport has played a big role in this, as any collegiate football fan knows.

As part of its persistent effort to fit in, Notre Dame has invited six US presidents to speak at commencement and has conferred honorary degrees on nine. During my time there Ronald Reagan spoke in 1981, his first public appearance after the attempt on his life nearly two months earlier. In 1984 New York Governor Mario Cuomo, then a presidential aspirant, spoke at Notre Dame, making his notorious "I'm personally opposed, but. . ." speech with respect to abortion, thus antagonizing serious Catholics but receiving Fr. Hesburgh's blessing.

It is thus not surprising that Hesburgh's successor, Fr. John Jenkins, would invite the newly-elected president Barack Obama to speak at commencement this year. What he did not foresee is the controversy this would engender, thus bringing unwelcome negative publicity to the university and to him personally. Initially the Bishop of Fort Wayne and South Bend, John D'Arcy, signalled his disapproval and his intention to absent himself from the event, due to Obama's personal and political support for the pro-choice position on abortion. Many, if not most, of the other American bishops followed suit. Most dramatically, Harvard Law Professor Mary Ann Glendon, former US Ambassador to the Vatican, refused the Laetare Medal which she had been offered by the university.

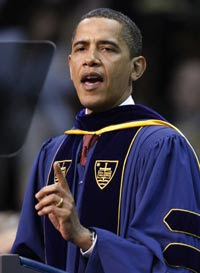

Obama's address can be seen here in full at Notre Dame's website. To those watching it, the audience's excitement at his presence was obvious. Some 54 percent of Catholics seem to have voted for Obama, and this is reflected in the enthusiastic reception he received. As is his wont, Obama gave a great speech and, knowing his audience, mentioned the 91-year-old Fr. Hesburgh's role in President Eisenhower's Civil Rights Commission and in the eventual passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. This magnificent gesture could only endear him to the Notre Dame community, which responded with applause throughout. As for the pro-life protesters who disrupted the event, they came off looking very rude indeed.

The controversy raises at least three issues worth addressing here.

First — and I say this as a Reformed Christian — it is not especially healthy for a university's decisions to be subject to a bishop's veto. A university, even an overtly confessional university, has its own authoritative sphere that ought not to be confused with that of the institutional church. I am with Abraham Kuyper in believing that a christian university best functions free from the unwarranted interference of church and state alike. That said, in this case the diocesan bishop made no pretence of vetoing Jenkins' decision; he simply elected to stay away.

Second, at one time Notre Dame was controlled by an otherwise little known order, the Congregation of the Holy Cross (CSC). Although the university is now governed by a lay board, its self-definition as a Catholic university implies a fidelity to the teachings of Rome. Up to now the president has always been a CSC priest. The very nature of Roman Catholicism implies, not just a confessional orientation, but fidelity to the claims of a particular institutional manifestation of the church. That church has made clear its teachings on the sanctity of human life, and thus the university is presumably bound by them. At the very least, Fr. Jenkins put the American Catholic bishops in a difficult position and forced them to respond in some fashion. Had he invited Obama to speak without offering him an honorary degree, he might have avoided the fuss.

Third and finally, in trying to solidify its place as an American university at home with the larger educational establishment, is Notre Dame in danger of losing its soul, if I may be permitted that overused cliché? Might its quest for respectability come at the expense of its Catholic identity? Of course, Notre Dame is not alone in this, as there are many christian universities in North America, some church-related and some not, that must daily confront this very issue. Shall such universities, for example, simply accept the larger definitions of the academic disciplines, their subject matter, their preferred methods, their general orientations, and so forth? Or are they obligated to subject even these to a biblically-shaped worldview? From my own experience at Notre Dame, it's not clear to me that this way of phrasing the issue would make much sense to people there. In a Catholic milieu the question would once again revolve around church teachings, which, as noted above, are clear on this particular issue while remaining silent on much else.

Whither Notre Dame? I think we can safely say that it will continue to be a force to contend with in the world of football. It is also likely to keep the undying loyalty of Domers past and present, who give generously to their alma mater. But it's an open question whether Notre Dame will survive over the long term as a genuinely Catholic university or, in the short term, whether Fr. Jenkins will keep his job after his inept handling of this fiasco.

No comments:

Post a Comment